日本ラジオ博物館補遺。

日本ラジオ博物館補遺。

最初の写真はトヨタ自動車が刈谷工場(現在のデンソーの刈谷工場)で作っていたラジオです。戦後すぐは車は軍需品ということでGHQに製造を禁止されていたので、やむを得ずということで、トヨタ自動車でもラジオを作ったということです。当時の電気系のエンジニアであればラジオを自作する人は多くいて、作るのはそんなに難しくなかったみたいです。そういうラジオはコストは高いけど概して品質は良かったとのことです。出光興産の創業者について書いた「海賊と呼ばれた男」でも、出光が戦後すぐ売りたくとも石油がなくて、やむを得ずラジオの修理を始めたというのがありました。

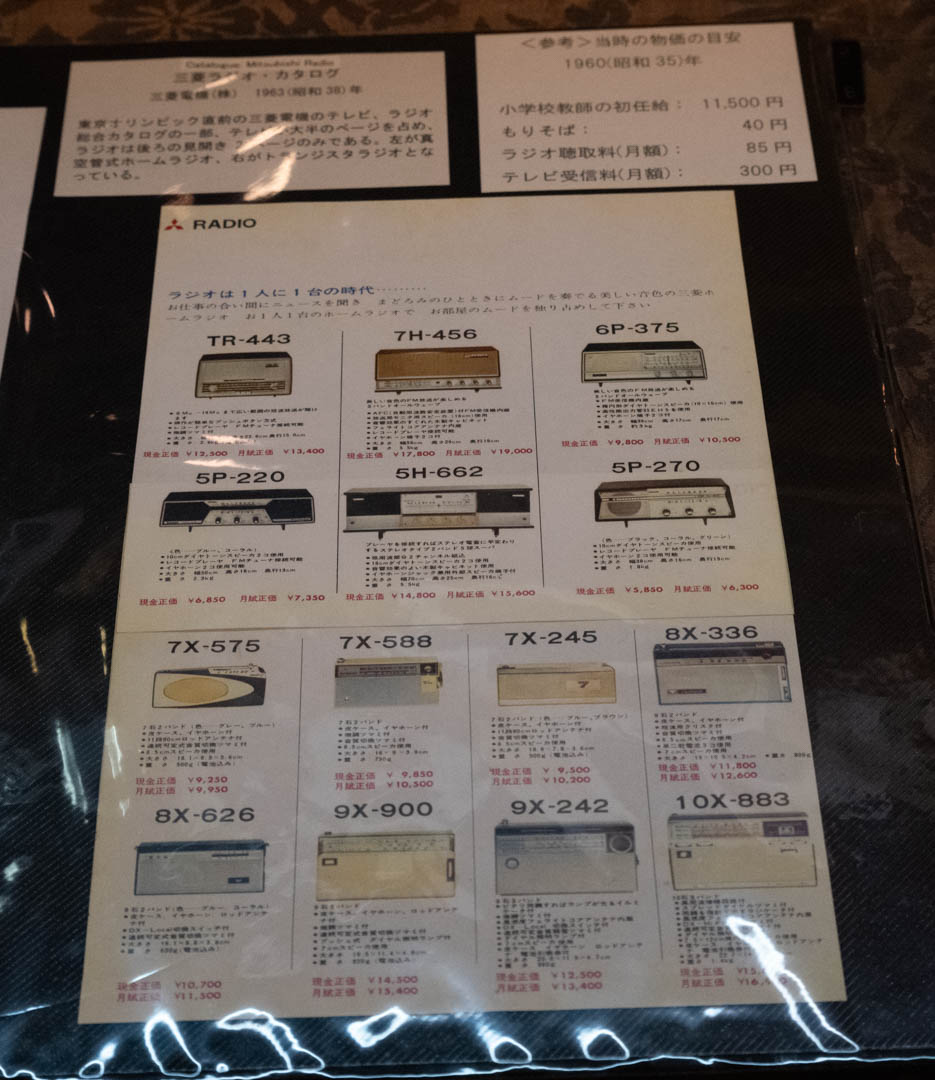

もう一つは、三菱のラジオ。三菱がラジオをやっていたなんて、まったく記憶にありませんが、このカタログを見る限り、かなり幅広く製品を出していたんですね。

カテゴリー: Culture

日本ラジオ博物館(松本市)

今回の旅行は宿は白骨温泉から5Kmぐらい下った別の温泉宿に泊まりましたが、白骨温泉を観た後、松本市に出かけました。何故かこの松本とは縁があり、今回が4回目の訪問になります。一番最初は1991年ぐらいだったかと思いますが、その当時Nifty Serveというパソコン通信のサービスの中に、日本語変換のWXシリーズを開発していたエー・アイ・ソフトのフォーラムがあり、私はそこの初期の常連でした。その当時オフ会(これも説明しておかないと死語かもしれませんが、パソコン通信の常連がいつもはオンラインで会話を交わしているのを、直接集まって飲み会などを開くのをオフ会と言っていました。オンラインの「オン」の反対で「オフ」ということです。)がエー・アイ・ソフトのオフィスがある松本市で開かれ、参加したのが最初です。その常連の中にはSF作家の高千穂遙さんなどもおられ、温泉に行って一緒の湯船に浸かったという思い出があります。

さて、そういう訳で松本城などは前に観ているので、今回時計博物館というのに行ってみました。そうしたらそこの地図に近くに「日本ラジオ博物館」というのがあるのが分かりました。「ラジオ博物館」と聞いて、元ラジオ少年が胸がときめかない筈はありません。13時から開館という不思議な開館時間でしたが、行ってみて大正解でした。たまたま最初は私一人が見物人だったため、館長の岡部匡伸さんの懇切丁寧な解説をたっぷりと聞かせていただくことが出来、大変参考になりました。(以下写真はすべてクリックで拡大します。写真撮影については許可をいただいています。)

最初の写真は、1925年頃の、玉電社という会社の5級ニュートロダイン受信機です。(ラジオ

最初の写真は、1925年頃の、玉電社という会社の5級ニュートロダイン受信機です。(ラジオ

ニュートロダインというのはオーディオマニアにおなじみの言葉でいえばネガティブフィ

大きなダイヤルが3つあるのはすべてバリコン(バリアブル・コンデンサー、選局に使用

なお、この松本の地にラジオ博物館がある理由ですが、

(1)東京などの大都市にしか放送局が無かった時代に、高感度のラジオで長野で放送を

(2)長野市にもその後放送局が出来たが、松本と長野の間は50Kmあるため、依然と

(3)全体に長野県は山がちで電波状況が悪かった。

ということみたいです。

これは日本無線の単球式ラジオです。日本無線は現在無線機のメーカーですが、昔はラジオも作っていました。単球で検波だけを真空管でやるもので、強電波地域用で写真のようなレシーバーで聞くものでした。初期のメーカーとしてはこの日本無線と早川電気(シャープ)です。シャープはいわゆるシャープペンでスタートしますが、関東大震災でその工場が崩壊し、ラジオ製造に転じます。その後松下も参入します。日本のラジオは最初期段階では、日本放送協会の認定を受けた受信機だけが使えましたが、これが高価な上に技術の進歩に追いつけなくて性能が悪く、NECや沖電気といったメーカーはこの認定タイプのラジオを作っていましたが、その後認定が不要になって価格競争が激化するとついていけなくなり撤退します。このため日本ではアメリカのRCAや欧州のフィリップのような大手のラジオメーカーが育ちませんでした。

これは日本無線の単球式ラジオです。日本無線は現在無線機のメーカーですが、昔はラジオも作っていました。単球で検波だけを真空管でやるもので、強電波地域用で写真のようなレシーバーで聞くものでした。初期のメーカーとしてはこの日本無線と早川電気(シャープ)です。シャープはいわゆるシャープペンでスタートしますが、関東大震災でその工場が崩壊し、ラジオ製造に転じます。その後松下も参入します。日本のラジオは最初期段階では、日本放送協会の認定を受けた受信機だけが使えましたが、これが高価な上に技術の進歩に追いつけなくて性能が悪く、NECや沖電気といったメーカーはこの認定タイプのラジオを作っていましたが、その後認定が不要になって価格競争が激化するとついていけなくなり撤退します。このため日本ではアメリカのRCAや欧州のフィリップのような大手のラジオメーカーが育ちませんでした。

初期の真空管ラジオは直流で動き、また電圧を分けるための抵抗に良いものがなかったため、真空管を動かすのに必要な3種類の電源(A電源というフィラメント加熱用と、B電源というプレート用、およびBを反転させたC電源)をそれぞれ個別に供給するというきわめて原始的なことが行われていました。その電源は鉛蓄電池が使われましたが、やがて乾電池が使われるようになり、それを発明したのは日本人だということです。しかし、その乾電池もかなり高価であり、いずれにせよ庶民にとっては高嶺の花でした。

初期の真空管ラジオは直流で動き、また電圧を分けるための抵抗に良いものがなかったため、真空管を動かすのに必要な3種類の電源(A電源というフィラメント加熱用と、B電源というプレート用、およびBを反転させたC電源)をそれぞれ個別に供給するというきわめて原始的なことが行われていました。その電源は鉛蓄電池が使われましたが、やがて乾電池が使われるようになり、それを発明したのは日本人だということです。しかし、その乾電池もかなり高価であり、いずれにせよ庶民にとっては高嶺の花でした。

これは松下(パナソニック)が作った最初のラジオです。日本放送協会の東京放送局が実施したコンテストにある別の機種と同じく一位になります。しかし性能を上げるためにコストがかさみ、値段が高すぎてあまり売れなかったそうです。パナソニックの社史には必ず登場するそうです。

これは松下(パナソニック)が作った最初のラジオです。日本放送協会の東京放送局が実施したコンテストにある別の機種と同じく一位になります。しかし性能を上げるためにコストがかさみ、値段が高すぎてあまり売れなかったそうです。パナソニックの社史には必ず登場するそうです。

これは戦後になって作られた、スーパーヘテロダイン方式の高級機で、何と5局がプリセットになっています。しかし実際には2種類あって、低価格の方はプリセットは表示だけで実際はロータリスイッチで切り換え、高価格の方が直接プリセットの表示部を押して切り替えるようになっていたようです。

スーパーヘテロダイン方式とは、ラジオ少年には常識でしたが、ラジオの電波が高周波のままだと増幅するのが難しいので、一度中間周波数という低い周波数に下げてから増幅する仕組みです。この方式はトランジスタラジオになってもそのまま使われていました。

そして1955年、東京通信工業(現ソニー)が最初のトランジスタラジオであるTR-55を発売します。価格は実に19,800円で当時の初任給の倍以上ですから、今で言えば50万円くらいの感じです。それだけ高い割りには5石で感度も音質も不十分であまり売れなかったようです。しかしその後トランジスタラジオの低価格化と高性能化は進み、その内日本の輸出におけるドル箱商品となり、アメリカとの間で貿易摩擦を引き起こします。その当時ラジオ用のトランジスタは国内ではほぼソニーが独占(元の技術はウェスタン・エレクトリックからの技術供与)していたみたいで、他の会社もトランジスタはソニーから買っていたみたいです。

これは、初期の真空管ラジオの中を見せるスケルトンモデルです。

これは、初期の真空管ラジオの中を見せるスケルトンモデルです。

この配線の仕方、今から考えると信じられないような方式です。ワイヤラッピングですらなく、銅線でもない、金属片によるダイレクトな配線。ベースになっているボードについてベークライト板みたいな絶縁板なのかと思ったら、木材で、元々アメリカでパンをこねるのに使っていた板をそのまま使ったそうです。今、電子回路の実験を行うため、部品取付け穴がいっぱい開いていて、短いリード線で配線する「ブレッドボード」というものがありますが、これは元々Bread boardであり、このパンこね板から名前が来ているんだそうです。

このページをお借りして、岡部館長に感謝申し上げます。

Wikipedia編集情報

Wikipediaの砥石の項の「分類」の所を丸々追加しました。

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%A0%A5%E7%9F%B3#%E5%88%86%E9%A1%9E

また、「革砥」の項、ほんの数行しかありませんでしたが、全面的に書き直しました。

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%9D%A9%E7%A0%A5

こちらは各国語のページの中で、一番情報量が多いです。

“An oyster of a man”の出典

「新々英文解釈研究」の最初の方に出てくる、”He is an oyster of a man.”の出典と思われるものを突き止めました。(OEDでのoysterやclamで「寡黙な人、非社交的な人」という意味の用例がマーク・トウェインが多かったので、最初マーク・トウェインの何かの作品かと思って、マーク・トウェイン作品のテキストが検索出来るページで調べましたが見つかりませんでした。)John Dunlopというスコットランドの詩人(1755 ー 1820)の書いた歌詞の中に”an oyster of a man”が出てきます。しかし、これは1812年の「ジョージ・マッカルがグラスゴーの『牡蠣クラブ』から引退するにあたって」という歌であり、かなり特殊な文脈で使われていることが確認出来ます。しかもおそらく、ジョージ・マッカルという人は何らかの理由で、「牡蠣クラブ」から引退(または退職)するのであり、そこで「牡蠣のような人」というのは「牡蠣クラブを象徴するような人(または常連客、あるいは従業員)」という意味でほとんどジョーク的に使っていると考えられ、「寡黙な人」という意味ではないように思います。歌詞の中に「白鳥のように自分自身のレクイエムを歌う」とありますから、ますます無口であるという解釈はおかしいです。それに「牡蠣クラブ」はおそらく美味しい牡蠣を食べながら社交を楽しむ人の会かあるいはオイスター・バーの名前ではないかと推察されます(現在でも同名のオイスター・バーが各地にあります)ので、まったくもって「寡黙な人」はおかしいと思います。ちなみに、歌詞の中の”Tiny Lochrians ! huge Pandores !”はどちらも牡蠣の品種だと思います。(前者はOEDに載っていませんが多分「Ryan湖(Loch Ryan、塩水湖)の牡蠣」ということだと思います。18世紀の始めから牡蠣の養殖場で有名のようです。後者は”A kind of large oyster found in the River Forth, esp. near Prestonpans.”とあります。)ジョージ・マッカルは、そういう色んな牡蠣に愛される人間だけど牡蠣みたいな人、って言っているんでしょうね。調べてみたらスコットランドのグラスゴーは今でも牡蠣で有名で色んなオイスター・バーやレストランがあり、そういう町で「牡蠣のような人」というのがネガティブな意味では決してないと思います。

John Dunlop (writer)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dunlop_(writer)

“Dunlop of that ilk : memorabilia of the families of Dunlop … ; with the whole of the Songs ; and a large selection from the poems of John Dunlop”

ON GEORGE M’CALL RETIRING FROM THE “OYSTER

CLUB” IN GLASGOW (1812).

[His letter of demission ended with four verses wretched poetical lines.]

The Oyster Club, in sable clad,

Laments for George M’Call,

Who, swan-like, his own requiem sings.

Weep ! Weep ! ! ye oysters all.

Tiny Lochrians ! huge Pandores !

Forget him, if you can ;

He was, creation must confess,

An oyster of a man ! !

拙試訳

牡蠣クラブ、喪服を着て

ジョージ・マッカル氏を悼む

氏は、白鳥のように、自分自身のレクイエムを歌う

ああ悲しい、悲しい、牡蠣のみんなよ

小さなリャン湖の牡蠣、大きなパンドレス牡蠣よ

もし可能なら彼を忘れよう

氏は、創造主は告白しなければならないが、

まさに人間牡蠣だった。

Festivals (Senteisai in Shimonoseki city)

The following essay is what I wrote as an assignment for a writing course at an English school AEON:

Topic: Festivals

Style: Casual

I would like to introduce a famous festival held during the so-called golden week in Shimonoseki city, my birthplace. The name of the festival is Senteisai (a festival for the passed emperor) held from May 2 to May 4. The purpose of the festival is to pacify the spirit of the emperor Antoku who died young in 1185.

In late 12th century Japan, two dominant samurai families, Genji and Heike fought each other trying to get the governance of Japan. The battle of Dannoura was the last one where Genji defeated Heike completely on the Kanmon channel. It was a naval battle where many ships of the both sides fought on a very narrow channel called Kanmon channel between Honshu and Kyushu. In the first stage of the battle, Heike had superiority, but because of the change of tide, Genji finally destroyed most ships of Heike. The emperor Antoku, who was a grandson of Kiyomori Taira of the Heikes and was just 6 years old at the battle, was getting on a ship with some female retainers. Most remaining samurai and retainers drowned themselves. The young emperor asked to a female retainer where they would go. She replied that they would go to the paradise and there was another metropolis at the bottom of the sea. Then, she brought him into the sea.

Some menials were drawn up from the sea and survived. Many of them were forced to do prostitution to make a living. Later they started to hold a festival to comfort the spirit of the late emperor. That was the start of Senteisai. The most spectacle attraction on the festival is a parade of beautifully attired geisha girls called “joro dochu”. (Joro is another name of geisha in Japanese.)

It is alleged and also believed that it surely rains on at least one day among the three. We call it the tears of Heike people.

Lafcadio Hearn, aka Yakumo Koizumi in Japan, wrote a story of Miminashi Hoichi (Hoichi the earless). Hoichi was blind and was a story teller of the battels between Genji and Heike, accompanied by the biwa, a Japanese lute. He was favored by some ghosts of Heike. Whenever he told the story to them, all the ghosts cried harshly at the scene of the death of the young emperor. A famous priest tried to save his life and wrote holy scripts of Buddhism on all parts of his body. But because the priest failed to write them on Hoichi’s ears, his ears were found and taken by the ghosts. He survived, but later he was called Miminashi Hoichi, Hoichi the earless.

ディープな徳島弁

ちょっと思う所あって、以前1996年から2005年まで9年間勤務した会社(本社は徳島市)での業務ノート(9年間で実に70冊)を見ていたら、まだ徳島で働き始めて1ヶ月くらいの時に、その業務ノートに何故か以下のようなディープな徳島弁が書いてありました。

ちょっと思う所あって、以前1996年から2005年まで9年間勤務した会社(本社は徳島市)での業務ノート(9年間で実に70冊)を見ていたら、まだ徳島で働き始めて1ヶ月くらいの時に、その業務ノートに何故か以下のようなディープな徳島弁が書いてありました。

あばさかる、あるでないで、行っきょった、いけるで、いっちょも、えっとこと、おじゅっさん、おっきょい、おもっしょい、かんまん、きぶい、くわる、ごじゃ、しにいる、しらこい、じるい、たっすい、ちっか、つくなむ、つまえる、どちらいか、とろくそだま、へちる、まけまけいっぱい、むつこい、やりこい

この中でまあ分かるのは、

あるでないで→あるでしょう

行っきょった→行ったんだよ

いっちょも→少しも、一つも

おじゅっさん→お住職、お坊さん

おっきょい→大きい

かんまん→構わない

ごじゃ→いい加減なこと、出鱈目なこと

ちっか→竹輪

まけまけいっぱい→おちょこやコップに液体を注ぐ時にギリギリいっぱいまで

ぐらいです。

疑問なのは徳島で暮らし始めて一ヵ月くらいの段階で、こんなディープな徳島弁をどこで集めたのかということです。

後、このノートには書いていませんでしたが、「すっぺらこっぺら」も中々衝撃的な徳島弁でした。「ああ言えばこう言う」みたいな屁理屈をあれこれこねる、といった感じでしょうか。

「令和」は元号のキラキラネーム

「令和」ですけど、私は元号のキラキラネーム化じゃないかと思います。まず出典が万葉集の梅花の歌とされていますが、正しくなく、実際には32首の梅花の歌がどういう時に詠まれたかを説明した漢文で書かれた前文に過ぎません。しかも元号にはそれなりに意味があって「平成」の時は「地平らかに天成る」(書経)から取ったと説明されていました。しかし今回のはまず「令」が単なる次に来る名詞を美化する接頭辞に過ぎず、それ自体の意味が希薄です。「初春の令月にして、気淑く風和ぎ」の文から2つの漢字を抜き出しただけで、こんなのが出典とそもそも言えるのでしょうか。要するに2つの漢字で見た目と響きが良いのを組み合わせたというだけで、そういう意味ではキラキラネームとほとんど変わりません。そして今回の選定のメンバーが林真理子とか山中教授とか、漢字の知識に乏しい人が多数混じっています。その場合に、意味とかを深く考えないで語感優先に傾いたのだと思います。

また、「令和」の出典になった「令月」が国語辞書に載っているので今でも使われていると判断している人がいますが、少なくとも私は今まで「令月」が使われている明治以降の文学作品を見たことがありません。Googleのサイト指定検索で青空文庫の全体を検索しても、一件もヒットしません。また、国語辞書の「令月」の説明は各社横並びでほとんど同じであり、これはおそらくある最初に載せた辞書の記述を他の辞書がぱくっているということです。辞書の意味記述は、普通用例を集めてその使われ方を分析するのですが、青空文庫でも一件も用例がないのであればその作業が出来ません。なので他の辞書に書いてあるのをパクるということになります。

それから、令室、令息のような「令」の使い方は、本来良くも悪くもなるものに付くのであり、その意味で「令月」は問題ありませんが、「令和」のように、本来いい意味しかない言葉に付くのは違和感大です。「令善」とか「令美」がないのと同じです。2つの漢字の熟語としてはほぼ成立しえない組み合わせです。そういう意味でも子供の名前を付ける感覚に近いです。

新元号について

令和って要するに昭和Ver.2なんでしょうか。「昭」は「てりかがやいて明らかなこと」で、令和の「令」も「令室」とかの「令」で「美しい」といった意味でしょうから、ほとんど変わらないように思います。そのうち、「令和」ではなくて「後昭和」とか呼ばれるんじゃ。

英語の同語反復を避けるルールについて

例の英語の「同じ単語を一つの文章の中で繰り返さない」という暗黙のルールですが、ネットで調べた限りでは、このルールは元々フランス語のもののようです。ご承知の通り、中世ではイギリスとフランスは同じ王によって治められ、多数のフランス語の語彙が英語に流入している訳ですが、当然上流階級が話す言葉がフランス語であれば、英語にもフランス語の慣習が持ち込まれても何の不思議もありません。

例の英語の「同じ単語を一つの文章の中で繰り返さない」という暗黙のルールですが、ネットで調べた限りでは、このルールは元々フランス語のもののようです。ご承知の通り、中世ではイギリスとフランスは同じ王によって治められ、多数のフランス語の語彙が英語に流入している訳ですが、当然上流階級が話す言葉がフランス語であれば、英語にもフランス語の慣習が持ち込まれても何の不思議もありません。

つまりこのルールには最初から一種の鼻持ちならない階級意識みたいなものが随伴していると言えそうです。

他のイタリア語やドイツ語などでは、相手の疑問文中に出てくる単語を、答えの中では代名詞で置き換えるというのは非常によくあります。ですが、英語みたいに名詞を同じ意味の名詞で置き換えるなんてことは、私の知る限りほとんど出てこないですし、ドイツ語で卒論を書いた時にもドイツ人教師(複数)からそういう指導は一切ありませんでした。またドイツ語やイタリア語では名詞に性があり、代名詞もその性に合わせて語形が決まり、どの単語を指しているかの判定が比較的容易です。しかし英語の場合は人間を指している場合を除いて、名詞の性は明確ではないので、代名詞による判定は簡単ではありません。(例外的に、例えば船については女性扱いでsheで受けるとかありますが。原子力潜水艦シービュー号でも、シービュー号は常にshe/herと女性扱いで参照されています。例えばTake her up!は潜水艦を浮上させろ、という意味です。)

Eigoxの先生に聞いた所によると、通常の生活で使う語彙は高校までに習得するもので十分で、TimeやNewsweekやNew York Timesで使われる日常ではまず見ない奇妙な語彙は、基本的に大学に入る上でマスターしないといけないということみたいです。なのでネイティブも私が買ったような語彙増強本を買って必死に勉強して、やっとこれらの雑誌や新聞の語彙が理解出来るようになる訳です。私が何度も経験したのは、この手の雑誌や新聞に出てくる聞いたこともないような単語を辞書で調べてみると、多くは単純な意味に過ぎず他の単語で表現することが可能です。にも関わらずそういう語彙を使う一つの大きな理由として、この「同一単語の繰り返しを嫌う」慣習から来ているケースが多いということです。これらの語彙を知っているのは「大学で学んだインテリの証拠」ということになり、ここにもまたある種の特権意識が見られます。

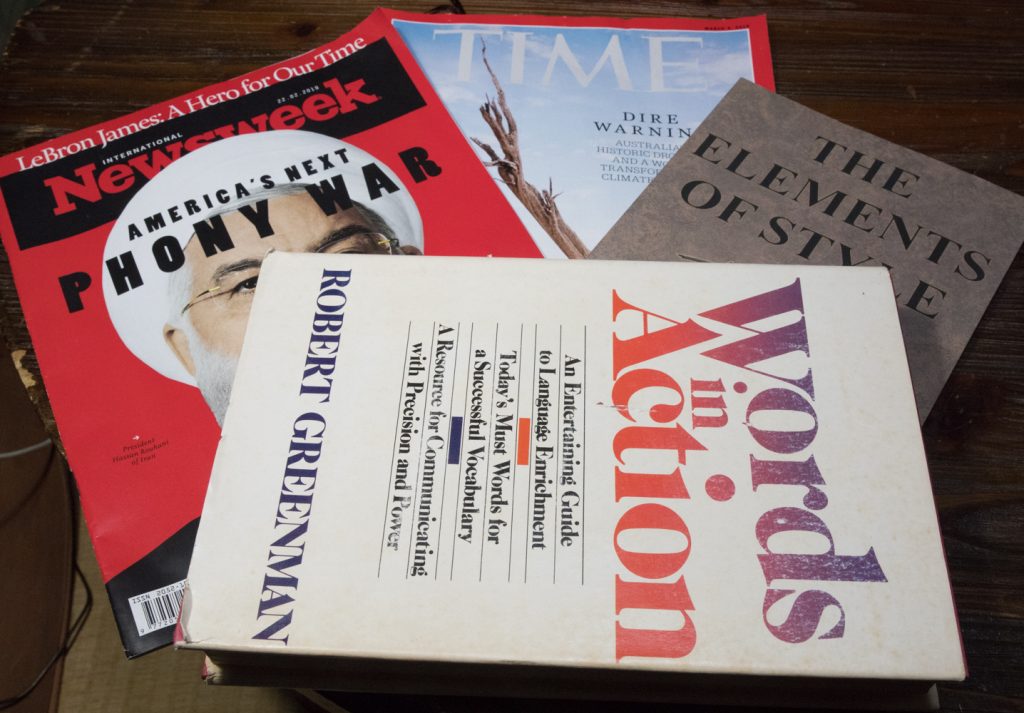

私は「同じ単語を繰り返さない」というルールについては、メリットとしては、微妙な意味合いを持つ概念を複数の言葉で描写して、その意味を分かりやすくさせる、小説などで読者を退屈させないようにする、ぐらいしか見つけられません。逆にデメリットは沢山あり、まず契約書や技術的文書のような曖昧さを嫌う文書ではまず適用出来ないというのが挙げられます。また言うまでもなく、文章の意味を曖昧にしかつ意味が明確に伝わるのを邪魔します。更には文章を書くのに余計な時間がかかります。(英語のシソーラスはほとんどこの目的で使われていると言っても言い過ぎではないと思います。)私はウィリアム・ストランク・Jrの”The Elements of Style”を持っていますが、このライティングの古典的教科書が言っていることは、「簡潔で、明確で、力強い文章を書きなさい」ということで、同単語反復禁止ルールはまさにその反対のことをやることだと思います。

What are your thoughts about the Japanese youth culture?/ About otaku culture in Japan

The following is my essay that I wrote as an assignment for an English school AEON:

Topic: What are your thoughts about the Japanese youth culture?

Style: Formal

Regarding the Japanese youth culture, the most important buzzword to describe it might be “otaku”. The Japanese word “otaku” is usually translated into English as “geek” or “nerd”. It is often alleged, however, each of them does not exactly reflect the true meaning of the original Japanese jargon.

The word “otaku” appeared first in some print media in the early 1980’s. It was almost the same time when many sub cultures became viral, especially comics and animations. Otaku, in the first place, was used to describe young people who are too enthusiastic about comics or animations. The original meaning of otaku in Japanese is a vocative expression of second person. The word is used for those who often try to talk to others starting with ”hey, otaku”.

Comics were popular even before World War II and the first TV animation started in Japan in 1963. After the tremendous success of an animation movie Space Battleship Yamato in 1977, the number of young fans of comics and animation skyrocketed and both genres became big industries. The word otaku appeared around this time.

At the first stage, the expression contained a rather negative connotation as they have interests only in virtual things and do not have much contact with the real world. This negative image was exacerbated when the Tsutomu Miyazaki incident happed in 1988 and in 1989. The criminal was 26 – 27 years old at that time and killed four female children aged from 4 to 7. By the investigation of the Japanese police, it was revealed that he was holding more than 5,000 video tapes of animation or drama. Most people related the image of otaku to him.

The image of otaku was gradually improved during the 1990’s and in some case the expression was used to describe somebody who has some sophisticated knowledge for something. The areas of interest did not stay only at comics or animation, but they spread to many genres such as computer, train, military, movie, Sci-Fi novels, camera, audio, and almost all sub cultures.

Currently, it is argued that otaku culture in Japan declined a lot while the Japanese government is bubbling over promoting otaku culture to foreign countries with a disgraceful copy “cool Japan”. (Who dares to say “I’m cool!”?) The main reason might be bad economical status of the younger generation.