これで多分本当に片付けの最後。白井喬二以外の大衆小説をまた棚を買ってまとめました。しかし「大菩薩峠」全20巻を含む文庫本が他に50冊くらいあって、それは入らずやむを得ず分散収納。ところで日本で大菩薩峠と富士に立つ影を両方最後まで読んだことがある人ってどのくらいいるんでしょうか。私の推測では万はいかないと思います。多めに見積もって数千人くらいかと。なお、国枝史郎については紙の書籍で持っているのは数冊ですが、実際にはKindle版で66冊持っていて全て読んでいます。

これで多分本当に片付けの最後。白井喬二以外の大衆小説をまた棚を買ってまとめました。しかし「大菩薩峠」全20巻を含む文庫本が他に50冊くらいあって、それは入らずやむを得ず分散収納。ところで日本で大菩薩峠と富士に立つ影を両方最後まで読んだことがある人ってどのくらいいるんでしょうか。私の推測では万はいかないと思います。多めに見積もって数千人くらいかと。なお、国枝史郎については紙の書籍で持っているのは数冊ですが、実際にはKindle版で66冊持っていて全て読んでいます。

カテゴリー: Public romance

白井喬二の「小説捕物にっぽん志」の書籍化

白井喬二の「小説捕物にっぽん志」が捕物出版という所から単行本化されるようです。歴史読本に連載されたものですが、玉石混交ながら中にはかなり面白い話もあります。

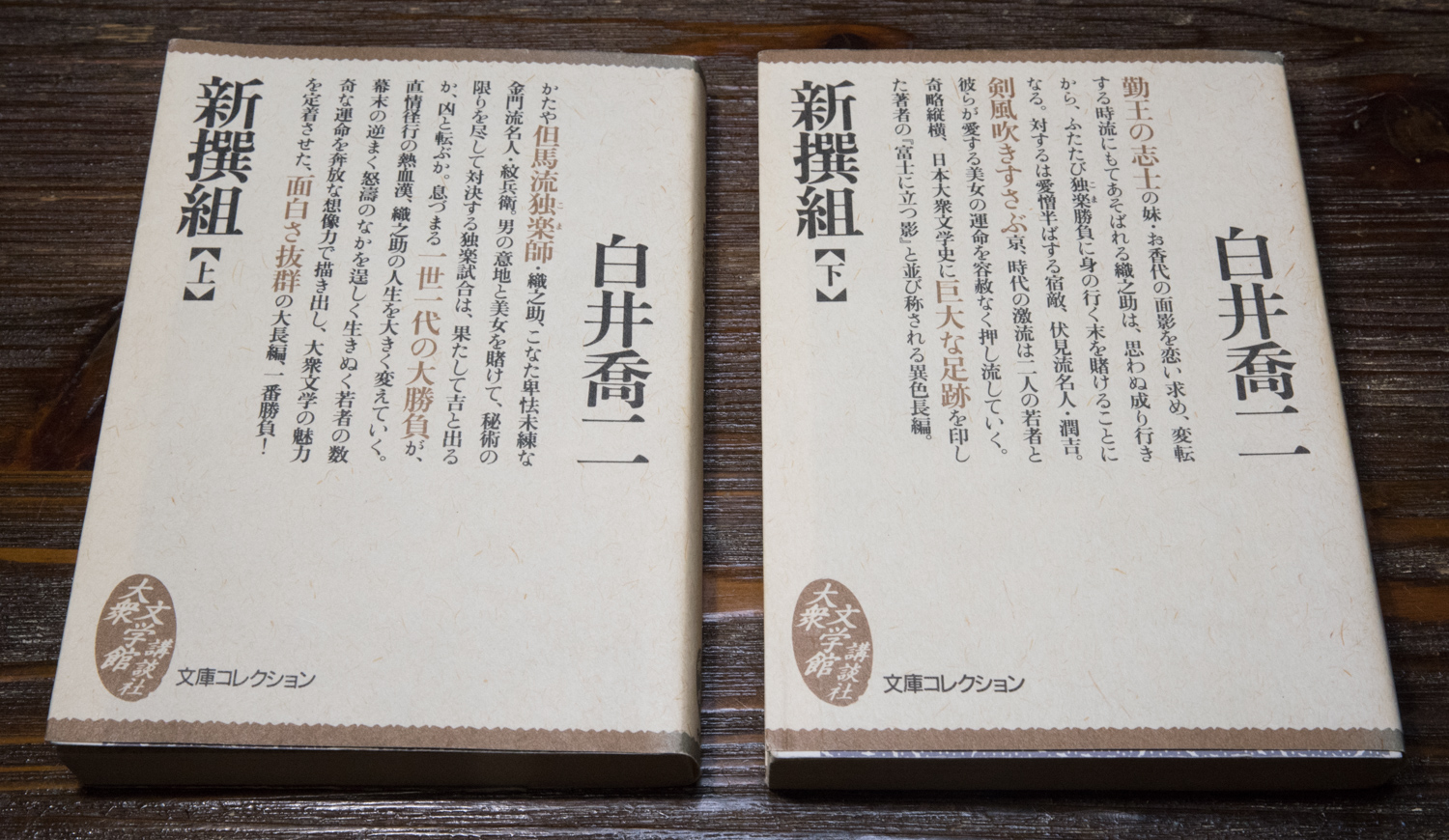

Kyoji Shirai: Shinsen-gumi

Shinsen-gumi was serialized from 1924 through 1925 on a weekly magazine “Sunday Mainichi”. Sunday Mainichi was published by Mainichi Newspapers Co., Ltd as the first weekly magazine in Japan. As the name shows, the magazine was first published as a Sunday issue of Mainichi newspaper. Since the distinction between normal newspaper and this weekly magazine was not clear for many readers, the number of prints remained stagnant in the early stage. The publisher then tried to make the contents of this weekly magazine clearly different from daily newspapers and it placed Kyoji’s new romance on the top of the magazine. It was a kind of gamble for the publisher, but very interesting stories of Kyoji’s novel attracted many new readers and the financial status of the magazine was thoroughly stabilized.

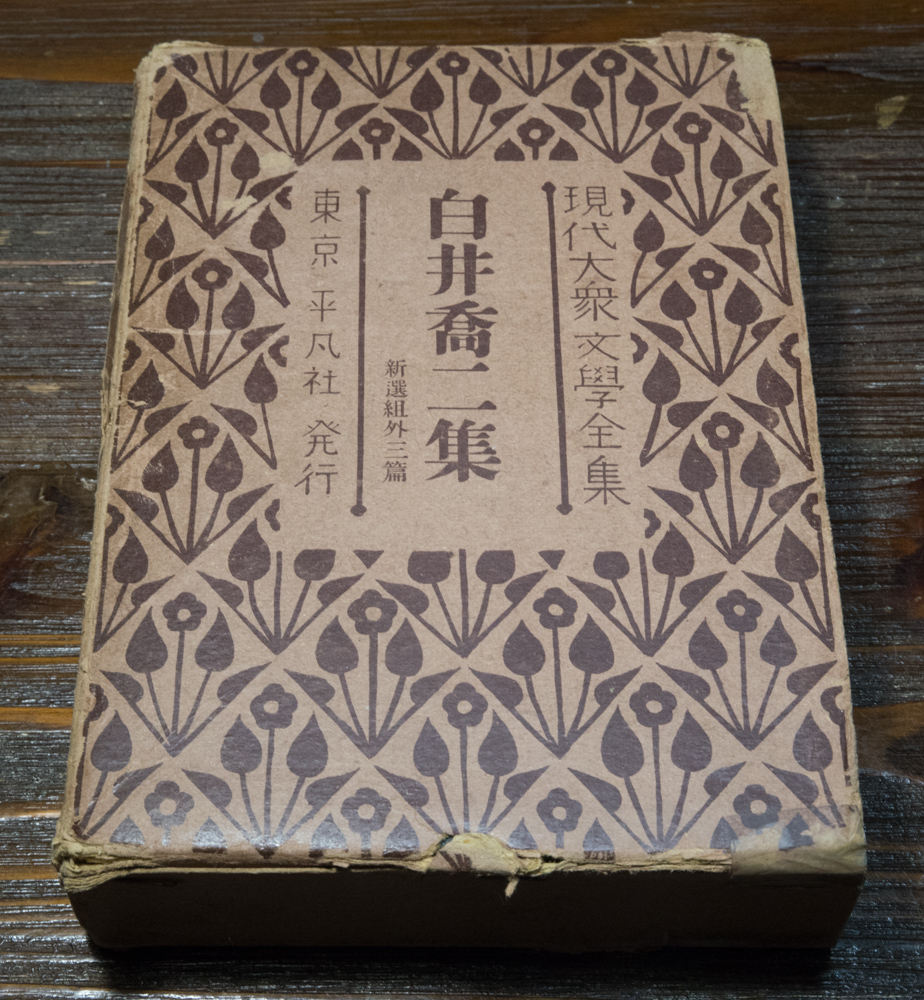

Another important topic related to this romance is that it was put in the first volume of the Heibonsha’s complete set of public romances, to which Kyoji committed himself very much. The fact that 330 thousands copies were sold for the first volume brought a big success to this set.

Shinsen-gumi was a group of Samurai warriors who guarded Kyoto under the authority of the Tokugawa Shogun regime from around 1863 through 1867. Many members of Shinsen-gumi took rather violent and brutal ways to guard Kyoto and killed many pro-Imperialists by their Japanese swords. Shinsen-gumi was one of the most favored topics for many novelists of public romance at that time.

Kyoji, however, did not write an usual story related to Shinsen-gumi. The story of the romance was mostly of battles between three different schools of spinning tops. Spinning tops were not only toys for kids but also a genre of street performance in Japan. A school of spinning tops here means combination of street performers and meister-level artisans. The first battle was between Orinosuke of Tajimaryu school and Monbee of Kinmonryu school. In this battle, two beautiful ladies were the prize of the battle, and the lady of the lost side had to be gifted to a foreign merchant. The second battle was between Orinosuke and Inosuke of Fushimiryu in Kyoto. In the second battle, both participants tried to get the heart of a lady.

These battels of spinning tops described in this romance were technically very deep and enthusiastic. For example, the both sides selected very special types of wood for their tops and the battle started from guessing which type of wood the counterpart selected. Orinosuke used one very special wood growing on the Nokogiri-yama mountain in Chiba, while Monbee selected one growing on Ontake mountain in Nagano. The Monbee’s top could generate strange wind while it spins trying to weaken the rotation of the counterpart’s top. The Orinosuke’s top, however, was not affected by the wind from the Monbee’s top, since he used a special wood growing on Nokogiri-yama mountain. (It means that Monbee failed to presume the type of wood used for the Orinosuke’s top). This kind of “professional” battles between two craft-persons attracted the then readers much and made them excited.

On the contrary to the battles of tops, Shinsen-gumi plays only in the background of the stories. Orinosuke witnessed the famous Ikedaya incident in which Shisen-gumi killed many famous pro-Imperialists. Kyoji developed a new way of fights between appearing characters in a romance other than sword battles (Chambara). This can be compared to the fact that he adopted a battle by debates in Fuji ni tatsu Kage.

The impression of this romance to the readers was tremendous and people requested Kyoji to write another romance of this type and it distressed Kyoji later for a long period, since he was thinking that he was always trying to change his styles and did not want to stay at the same stage.

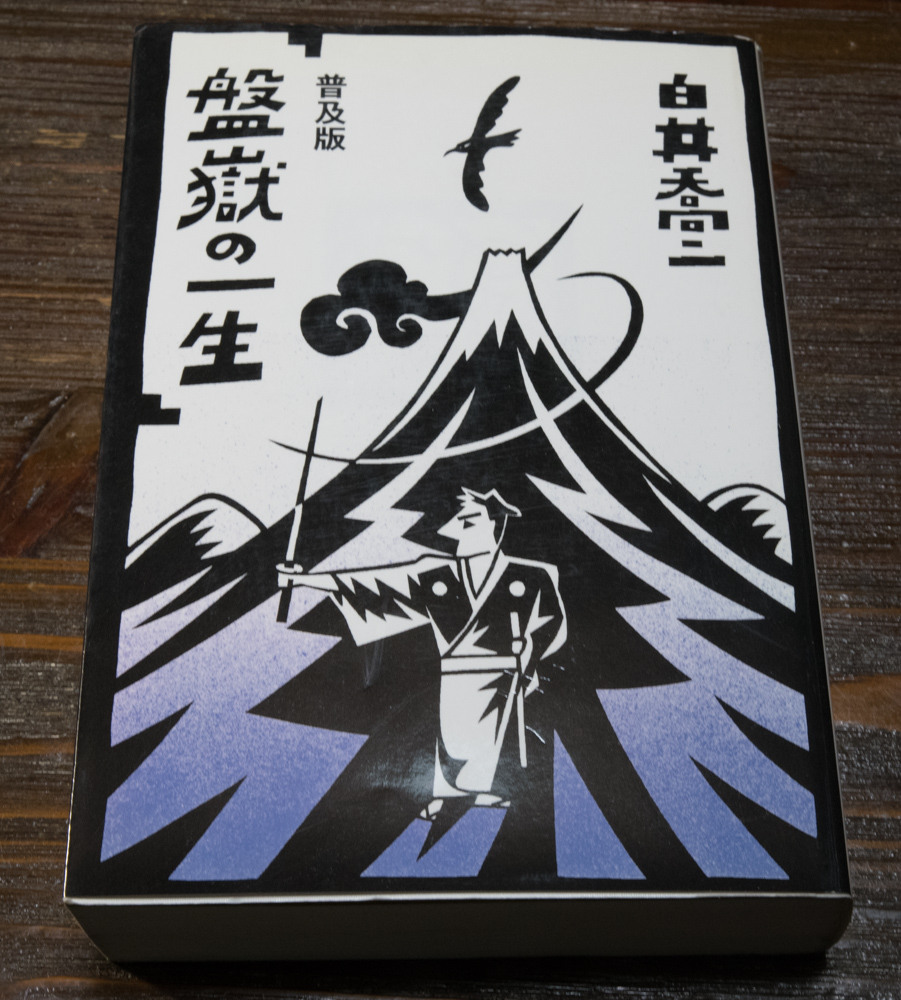

Bangaku no Issho (The life of Bangaku) by Kyoji Shirai

Let me introduce today one of the most impressive novels of Kyoji Shirai: Bangaku no Issho (The life of Bangaku, “盤嶽の一生”). This novel is a collection of short stories featuring Bangaku that Kyoji wrote for several magazines from 1932 to 1935.

Let me introduce today one of the most impressive novels of Kyoji Shirai: Bangaku no Issho (The life of Bangaku, “盤嶽の一生”). This novel is a collection of short stories featuring Bangaku that Kyoji wrote for several magazines from 1932 to 1935.

As the title shows, this novel describes the life of Bangaku Ajigawa (“阿地川盤嶽”), a lone wolf Samurai worrier, who loves rightness and always try to find it and is eventually betrayed. He was born in Bushu (the curent Saitama-Tokyo-Kanagawa area) and lost his father at 12 years old and his mother at 14. After the death of his parents, he was raised by his uncle, but because the daughter of his uncle (namely his cousin) disliked him much, he left his uncle’s house when he became an adult. Since his skill of swordplay reached the expert level when he was 26 years old, his master gave him a noted sword named Heki Mitsuhira (“日置光平”) .

As I wrote in my introduction of Kyoji Shirai’s life, Kyoji inherited the sense of justice from his father who was a policeman when he was born. Bangaku can be considered to be an alter ego of Kyoji. All Christians know the Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.” (Mattew 5.6, KJV). Bangaku is truly one of those who do hunger and thirst after righteousness. If he were a Christian, he might have been filled, but he was not.

Repeated stories of Bangaku that he expects righteousness and he is finally betrayed and disappointed are funny but sad at the same time. For example, when he was living in a slum of the Edo city, he sympathized with miserable workers of a match factory. Since he had some scientific knowledge, he tried to construct an automated machine of match production in order to reduce the heavy work of the workers. When the machine was completed, however, the owner of the factory fired many workers because he can save them by the power of the machine. If we see another example, Bangaku tried once a fortune-telling play by throwing some unglazed dishes (fortune is judged by how dishes broke) because he thought that such thing can be completely coincidental and no human malicious intention is included. The truth was, however, the fortune-teller was preparing several patterns of broken dishes in advance and was selecting the results according to the economical status of the customer.

Bangaku gradually lost any expectation for adults and started to hope for young people. But some young guys betrayed him bitterly and then he started to hope for children, or finally for babies. All his trials were not satisfactory at all.

These stories had not been finished. IMHO, the author, Kyoji, could not find out an appropriate end for these stories, or he might have thought that Bangaku, a kind of dreamer, should wander in the limbo between expectation and disappointment eternally.

This novel was picturized twice and made to a series of TV drama also twice.

The first movie was taken by Sadao Yamanaka in 1933. Sadao Yamanaka was a gifted movie director but died as a soldier in China at the age just 29. While Kyoji Shirai was not satisfied with most movies based on his stories, he evaluated the talent of Sadao Yamanaka very highly. Although the film itself was lost by war, there was a legendary scene in the movie where some thieves of watermelon (Bangaku was having his eyes on a watermelon field in the night) act like rugby players passing a watermelon from one to another. Kon Ichikawa, a Japanese movie director who picturized the first Tokyo Olympic in 1964, watched this movie of Bangaku when he was a child, and he scripted for the TV drama of Bangaku broadcasted in 2002. Bangaku was played by Koji Yakusho (“役所広司”).

Public romance in Japan (7) – Kyoji Shirai’s “Fuji ni tatsu kage”

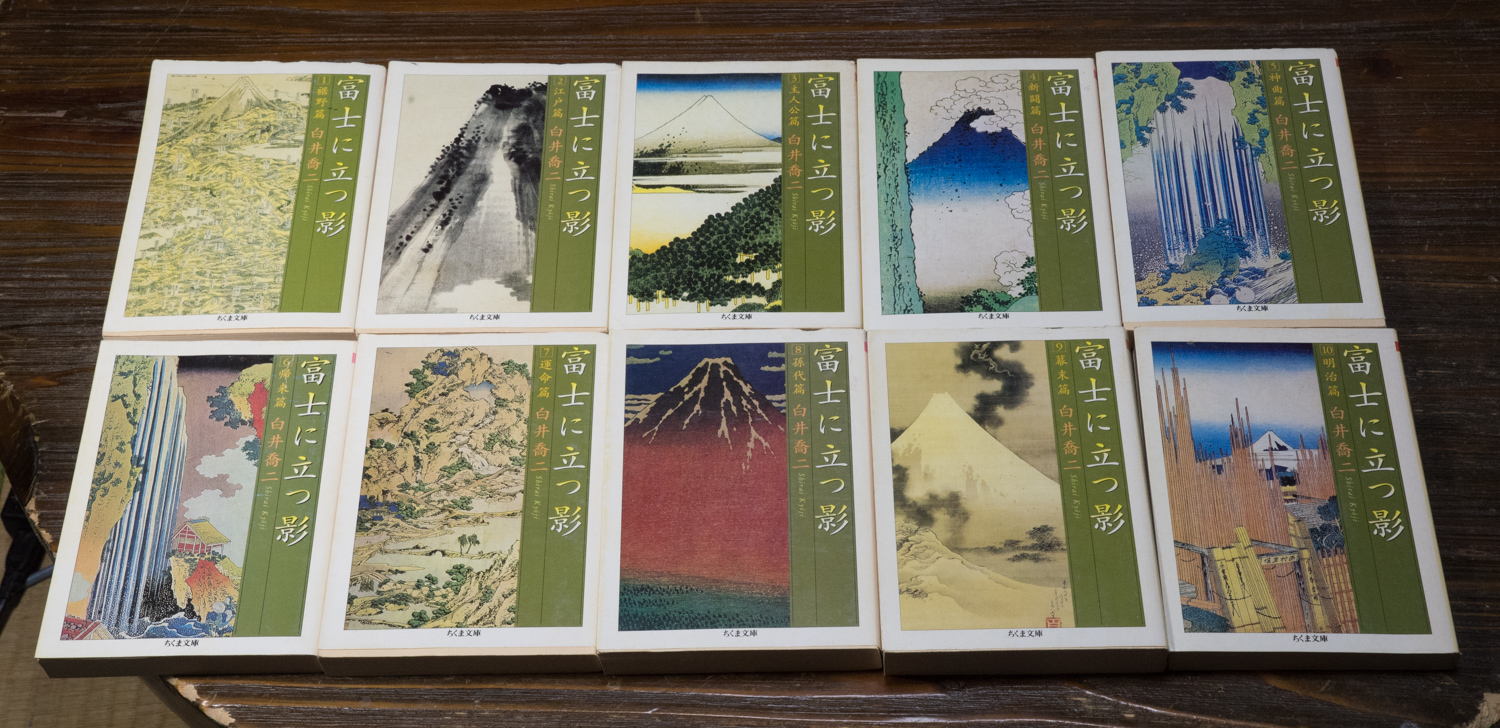

Let me introduce today Kyoji Shirai’s best romance, “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, a shadow standing on Mr. Fuji). This romance is not only his best work, but also a big milestone in the history of public romance, or even in all Japanese literature, I should say. The three greatest works in public romance are, “Dai Bosatsu Touge”, “Musashi” (“宮本武蔵”) of Eiji Yoshikawa (“”吉川英治”), and this work.

Let me introduce today Kyoji Shirai’s best romance, “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, a shadow standing on Mr. Fuji). This romance is not only his best work, but also a big milestone in the history of public romance, or even in all Japanese literature, I should say. The three greatest works in public romance are, “Dai Bosatsu Touge”, “Musashi” (“宮本武蔵”) of Eiji Yoshikawa (“”吉川英治”), and this work.

This romance was serialized in the newspaper “Hochi” (“報知新聞”) from July 1924 through July 1927, for more than 1,000 times. (Novels serialized in newspapers are still popular in Japan, but the average period of continuance is just around a half year.) There are ten volumes (also chapters) in Japanese paper book style, as you can see in the photo. The names of ten parts are, 1. Susono-hen (Chapter of the plain at the foot of Mt. Fuji), 2. Edo-hen (Chapter of Edo city), 3. Shujinko-hen (Chapter of the central character), 4. Shinto-hen (Chapter of a new battle), 5. Shinkyoku-hen (Chapter of Divine Comedy), 6. Kirai-hen (Chapter of coming back to Mt. Fuji), 7. Unmei-hen (Chapter of destiny), 8. Sondai-hen (Chapter of grandsons’ generation), 9. Bakumatsu-hen (Chapter of the end of Edo period), and 10. Meiji-hen (Chapter of Meiji period). The romance was sold for more than 3 million copies.

Let me introduce now basic story of this romance. To make a long story (literally) short, this romance describes 68 years’ (1805 – 1873) battles between two families of castle builders, during three generations, namely fathers, sons, and grandsons. The author said that he described “war and peace” based on humanity. The story starts when Tokugawa shogunal government planned to build a new castle in the plain at the foot of Mt. Fuji for the training of their subordinate soldiers in western style. The government summoned two engineers, namely Kikutaro Sato (“佐藤菊太郎”), as a representative of Sanshi-ryu (“賛四流”) school of castle building, and Hakuten Kumaki (“熊木伯典”), as one of Sekishin-ryu (“赤針流”), another dominant school of castle building. The government tries to determine the chief designer of the new castle by the competition between two schools. Until this work, most public romance used fighting by Japanese swords (Chambara) to solve the conflict between two parties. This work, however, adopted debates between two engineers, which was, and still is, a brand-new style. Kikutaro is a young, talented, and honest guy. Hakuten, an older guy, on the other hand, plays very dirty. Most readers expected the victory of Kikutaro, a white-hat, but the author betrays the readers’ expectation, which is very rare in public romance.

The actual hero of this romance appears at first only from the chapter three. The hero, Kimitaro Kumami (“熊木公太郎”) is the son of Hakuten, a quite evil guy. The son, however, is completely different from his father. He is quite honest, decent, always trying to protect the weak, and at the same time a little bit foolish. A critic compared him with Prince Myshkin in Dostoyevsky’s novel “The Idiot”. Both of them are, so to say, holy idiots. This character is quite new and different from the cruel, nihilistic character of “Ryunosuke Tsukue” in “Dai Bosatsu Touge”. This hero brought the romance into a big success, because many readers really loved the character of Kimitaro. In parallel to Kimitaro, Heinosuke Sato (“佐藤兵之助”), the son of Kikutaro, is described as a very smart, bureaucratic type, but rather cruel guy. This is quite a surprising twist that the good side and the evil side turn over in the second generation.

One English teacher at Eigox told me when I introduced this romance to him that this romance sounds similar as Frank Herbert’s “Dune”, which also describes the battles between two families, namely between the Atreides and the Harkonnens. In Dune, however, the Harkonnes are always described as the evil side. In Fuji ni tatsu kage, we cannot simply say that one side is good and the other is bad, and do not know until the end of the story how the battles between two families are settled. There is also a “Romeo and Juliet” type affair between the two families, which makes the story more complex and attractive. In such viewpoints, this romance goes far beyond the realm of usual public romance. Kyoji Shirai aimed at such a high-level literature even the genre was classified as public romance, which was usually considered as vulgar literature.

It is absolutely impossible to describe all charm of this romance here. I strongly hope that this novel will be translated into English for foreign readers someday.

Public romance in Japan (6) — The life of Kyoji Shirai and his works (2)

In 1925, he organized a party of public romance writers called “Niju-ichi-nichi-kai”, as I introduced in my fourth article. Soon after that, he collaborated with Heibonsha (“平凡社”), a publisher which was famous for the publication of an encyclopedia, in planning a new complete set of public romance dubbed “Gendai Taishu Bungaku Zenshu” (“現代大衆文学全集”, a complete set of modern popular literature), which was finally published in 40 volumes. (Later another 20 volumes were added, so the total volumes were 60.) The first issue (the volume one) was Kyoji’s “Shinsen-gumi” (“新撰組”), and around 330 thousand copies were sold. This contributed to the success of the set and appealed at the same time popularity of public romance. (At that time, since the sales profit of the first volume was used to publish the following volumes, the success of the first volume was quite important.) The royalties of this publication helped many public romance novelists economically. Among them, especially, Rampo Edogawa is alleged that he could build a new house by the reward of this set.

In 1935, Kan Kikuchi (“菊池寛”), the president of Bungei Shunju-sha (“文芸春秋社”), set up a literary award for public romance, named “Naoki prize” (“直木賞”) and Kyoji became one of the first judges and had continued that role until 1942.

Some of his other important works before the end of World War II were “Sokoku wa izuko he” (“祖国は何処へ”), which was his second quite long story, “Sango Jutaro” (“珊瑚重太郎”), or “Bangaku no issho” (“盤嶽の一生”, the life of Bangaku). The last one was picturized by Sadao Yamanaka (“山中貞雄”), who is famous for his last film Humanity and Paper balloon (“人情紙風船”), in 1933. Although the film was unfortunately lost by the war, Kon Ichikawa (“市川崑”), another famous movie director in Japan who picturized the first Tokyo Olympic, watched this movie and was very impressed when he was a kid, and he directed the TV drama of this novel in 2002.

The period after World War II was not a good time for Kyoji. For one thing, public romance was much damaged by the policy of GHQ (General Headquarters of the Allied Forces), which occupied Japan from 1945 through 1952, to prohibit expression to praise traditional morals in Japan, alleging that such morals fueled the Japanese ante bellum militarism. Secondary, people required simpler, much vulgarer novels which handle mostly sex-related matters after the end of the war. Not to mention Kyoji, most of other novelists of public romance suffered as well from these circumstances. They had to wait the revival of public romance in 1960’s. Kyoji, however, under such unfavorable conditions, has never stopped to release his novels. In 1970, when he was 80 years old, he was still serializing “Kokui Saisho Tenkai Sojo” (“黒衣宰相 天海僧正”, Priester Tenkai, a chancellor with black attire) in a Buddhism magazine named “Dai horin” (“大法輪”). Examples of his other important works after the war are, “Kirigakure Emaki” (“霧隠繪巻”), “Yukimaro Ippon Gatana” (“雪麿一本刀”), or “Kuni wo aisu saredo Onna mo” (“国を愛すされど女も”), etc.

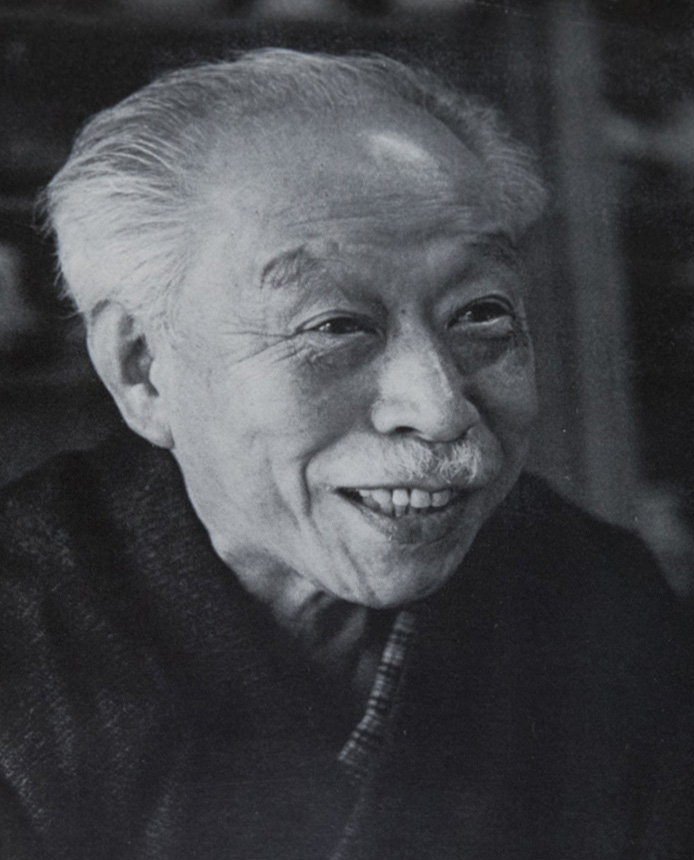

Kyoji died in1980, at age 90 at his daughter’s home in Ibaraki prefecture.

None of his works has been ever translated into foreign languages, regretfully to say. Around in 1928, however, Yale University in the USA contacted Kyoji asking to allow it the right of an English translation of “Fuji ni tatsu kage”. The university asked Kyoji to offer a digest version at around 40% length and he accepted that condition. He could not offer a digest version because of his busyness and the translation was not done accordingly, to our regret.

Public romance in Japan (5) — The life of Kyoji Shirai and his works (1)

As I stated in the previous article, Kyoji Shirai was one of the most important novelists in an emerging stage of public romance. Let me now describe his life and some of his works in detail.

Kyoji Shirai was born in Yokohama in 1889, as the first son of Takamichi and Tami Inoue, who were both from Samurai (warrior) class of Tottori prefecture. When he was born, Takamichi was working as a policeman of Yokohama city. Kyoji inherited the sense of justice from his father. Because of the frequent changes of his father’s working place, Kyoji kept on the move from Ome, Kofu, Urawa, and to Hirosaki in Aomori prefecture. In 1902, he finally settled in his parents’ home town, Yonago in Tottori. While he was attending Yonago east high school, he wrote two novels and they were put in two local newspapers, showing his precocious talent as a writer.

He entered then Waseda university but he soon moved to Nihon university by his father’s request that he should become a lawyer. While he was studying at Nihon university, he translated many works of Saikaku Ihara (“井原西鶴”) and Monzaemon Chikamatsu (“近松門左衛門”) into the modern Japanese for Hakubunkan (“博文館”), which was one of the biggest publishers at that time in Japan. These works gave him deep knowledge of the Japanese literature in Edo period, and he utilized many episodes or anecdotes in this period later in his works.

After he graduated Nihon university, he started to work at a few publishers and got married with Tsuruko Nakajima, a daughter of a baron Masutane Nakajima, in 1916.

In 1919, he wrote “Kai-kenchiku juni-dan gaeshi” (“怪建築十二段返し”) as his first work under the name “Kyoji Shirai” and the manuscript was offered to Hakubunkan. The publisher put the work in the January issue of “Kodan zasshi” (“講談雑誌”) in 1920. This first work was welcomed and he received requests for other works one after another. Ryunosuke Akutagawa (“芥川龍之介”) praised Kyoji’s “Ninjutsu Koraiya” (“忍術己来也”) enthusiastically and “Shimpen Goetsu Zoshi” (“神変呉越草紙”) also got a favorable reception.

In 1924, he started to write two most famous works, namely “Shinsen-gumi” (“新撰組”) and “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”), and established his fame by these two great novels. The former was put at the head of a weekly magazine “Sunday Maichini” (“サンデー毎日”), which was the first weekly magazine in Japan, and the magazine could get enough number of readers to survive as an independent magazine by his novel. The latter was serialized in the Hochi newspaper (“報知新聞”), which was one of the biggest newspapers at that time, and it continued for more than 1000 times. The hero in this novel, Kimitaro Kumaki (“熊木公太郎”), attracted the readers overwhelmingly by his honest and decent character. As I introduced before, Ryunosuke Tsukue (“机龍之助”) in Dai Bosatsu Touge (“大菩薩峠”) was the first typical character type in public romance with his nihilism and cruelty, but Kyoji created then a completely different type of bright character with this novel. (to be continued)

Public romance in Japan (4) — Kyoji Shirai and Niju-ichi-nichi kai

During an emerging stage of public romance, another outstanding novelist was Kyoji Shirai (“白井喬二”) (1889 – 1980). Not only he created some great works one after another such as “Shimpen Goetsu Zoshi” (“神変呉越草子”) (1922 – 1923), “Shinsen-gumi” (“新撰組”) (1924 – 1925), or “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, A shadow standing on Mt. Fuji) (1924 – 1927), he also started to use the word “大衆” newly as the translation of an English word “public”, adding it a new reading as “Taishu” instead of the conventional “Daisu” or “Daiju” that meant a group of Buddhist monks, and thus triggered that the word “大衆文学” (Taishu Bungaku, literature for common people) was created by the then media.

During an emerging stage of public romance, another outstanding novelist was Kyoji Shirai (“白井喬二”) (1889 – 1980). Not only he created some great works one after another such as “Shimpen Goetsu Zoshi” (“神変呉越草子”) (1922 – 1923), “Shinsen-gumi” (“新撰組”) (1924 – 1925), or “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, A shadow standing on Mt. Fuji) (1924 – 1927), he also started to use the word “大衆” newly as the translation of an English word “public”, adding it a new reading as “Taishu” instead of the conventional “Daisu” or “Daiju” that meant a group of Buddhist monks, and thus triggered that the word “大衆文学” (Taishu Bungaku, literature for common people) was created by the then media.

The reason I use “public romance” here is that the word “大衆” was originally the translation of “public” and most works appeared in this stage were to be regarded rather romances than novels.

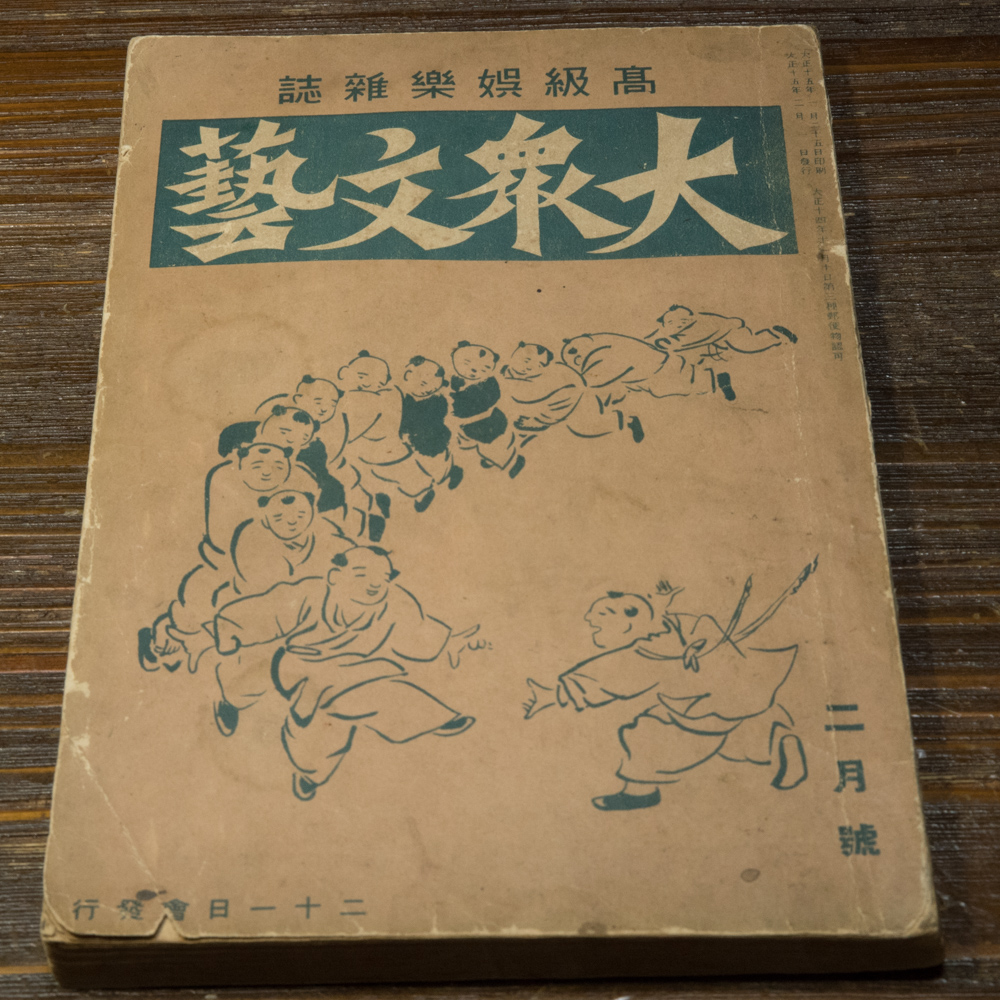

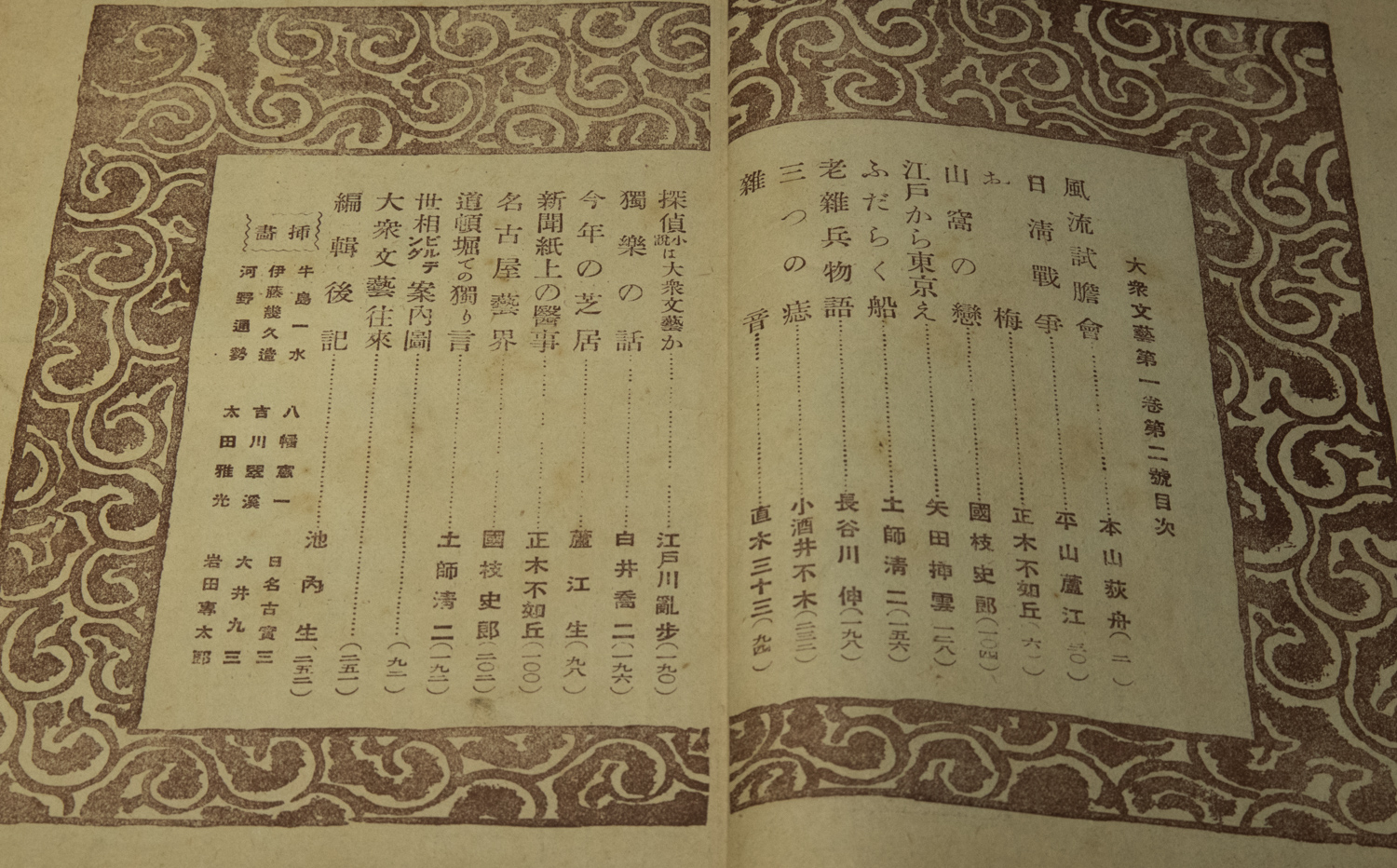

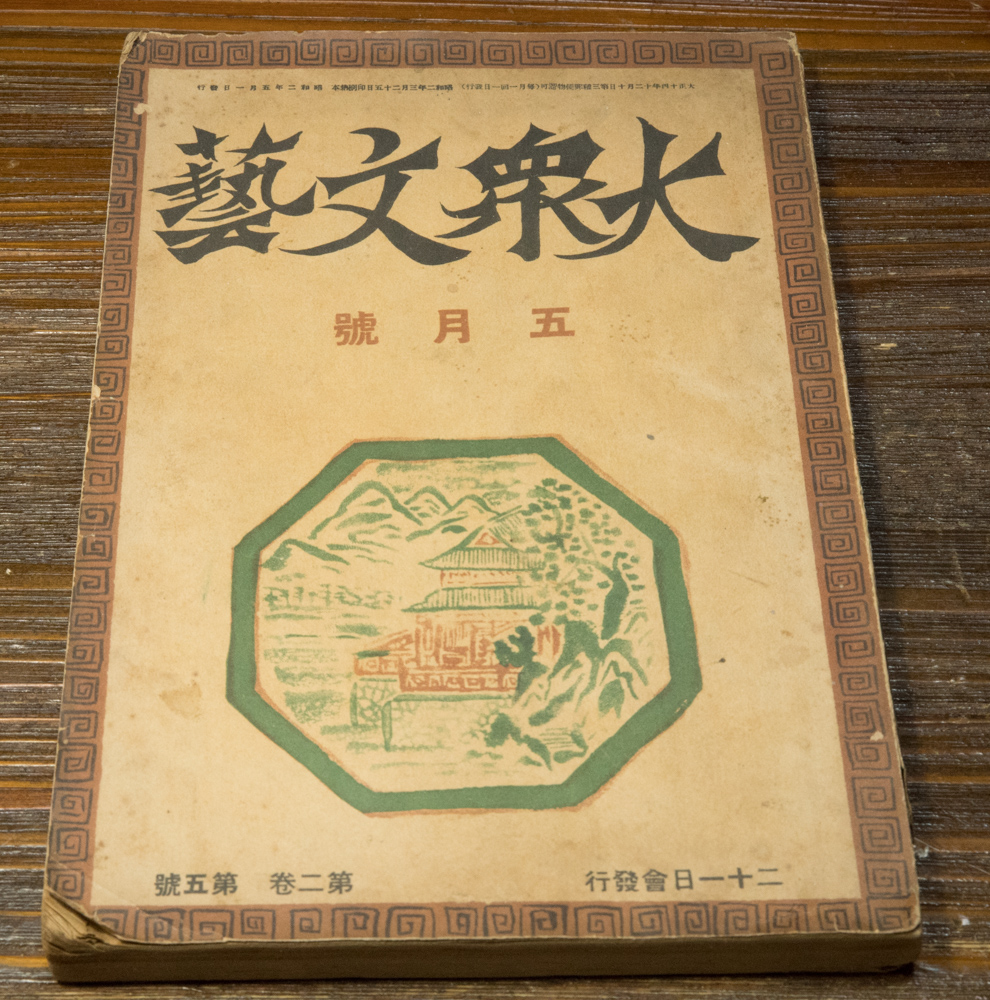

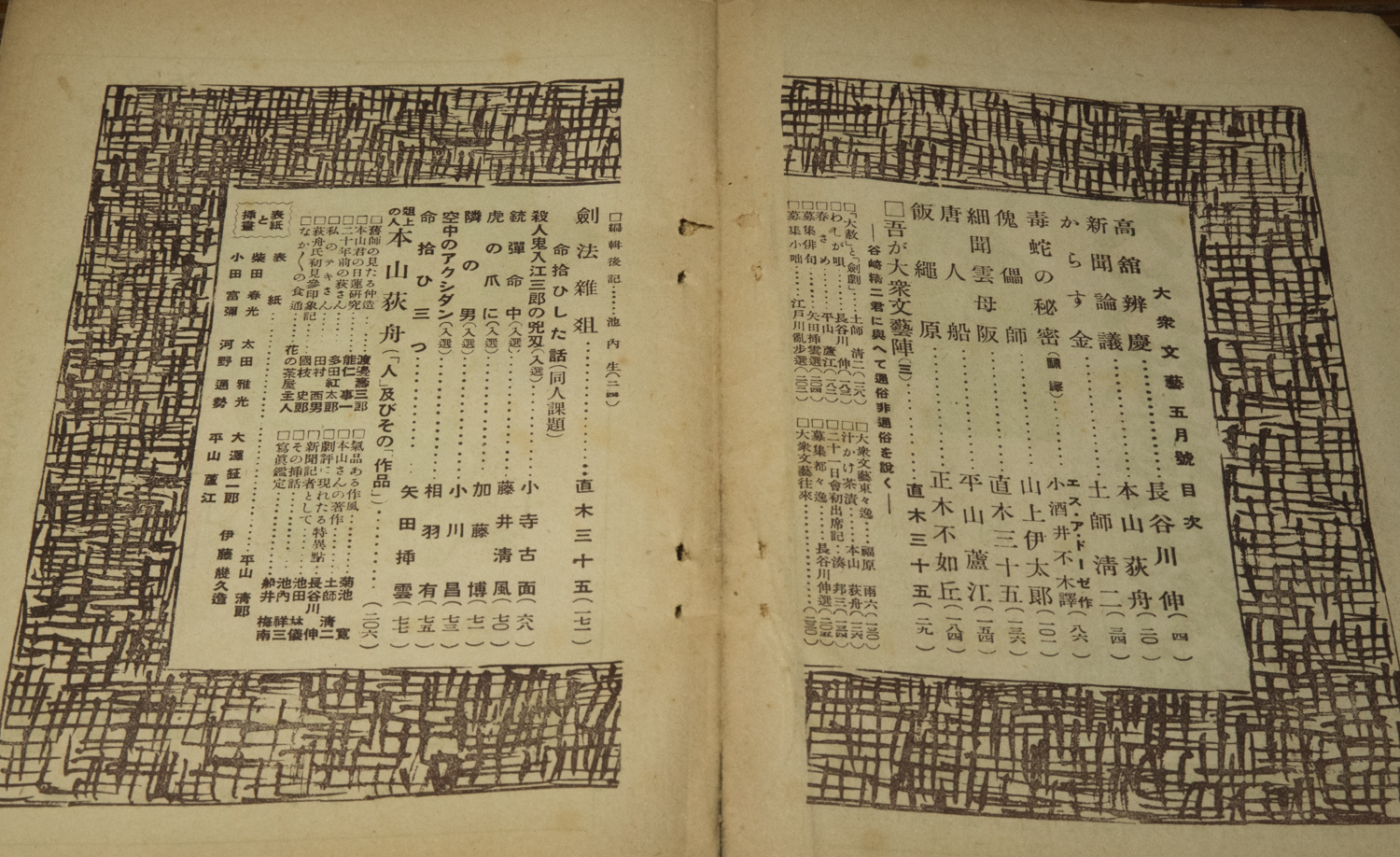

He also initiated a social gathering of public romance novelists in 1925 named “Niju-ichi-nichi kai” (“二十一日会”, a party of twenty first day). The members were, Kyoji Shirai, Shin Hasegawa (“長谷川伸”), Shiro Kunieda (“国枝史郎”), Sanju-san Naoki (“直木三十三”, he changed the name later to Sanju-go Naoki (“直木三十五”)), Rampo Edogawa (“江戸川乱歩”), Fuboku Kosakai (“小酒井不木”), Tekishu Motoyama (“本山荻舟”), Roko Hirayama (“平山蘆江”), Fujokyu Masaki (正木不如丘”), Soun Yada (“矢田挿雲”), and Seiji Haji (“土師清二”). Except Rampo, Fuboku, and Fujokyu, all of them were novelists of period romances. Although Rampo Edogawa was a writer of early-stage detective novels in Japan, that genre was also classified as a type of public romance at that time. From 1926, the party started to publish a magazine named “Taishu Bungei” (“大衆文芸”). (See the pictures.) With the magazine, they presented the emergence of a new genre in the Japanese literature.

Public romance in Japan (3) — Dai Bosatsu Touge

Everybody agrees that Kaizan Nakazato’s (“中里介山”) “Dai Bosatsu Touge” (“大菩薩峠”, Dai Bosatsu pass) is the first typical example of public romance in Japan, excluding the author himself. He did not accept at all that his novel is classified as a public romance, instead he called it a “Mahayana novel” (“大乗小説”). (Mahayana Buddhism is a school of Buddhism that was missionized in East Asian countries including Japan.)

Everybody agrees that Kaizan Nakazato’s (“中里介山”) “Dai Bosatsu Touge” (“大菩薩峠”, Dai Bosatsu pass) is the first typical example of public romance in Japan, excluding the author himself. He did not accept at all that his novel is classified as a public romance, instead he called it a “Mahayana novel” (“大乗小説”). (Mahayana Buddhism is a school of Buddhism that was missionized in East Asian countries including Japan.)

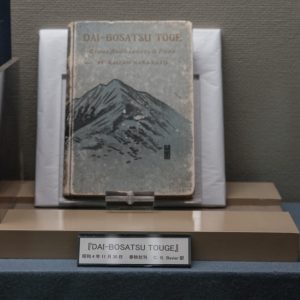

It is true that the novel is in many aspects beyond any classification. As you can see in the picture, it has twenty volumes in Japanese paper book style, and continued for 28 years (1913 – 1941) to write, yet is still uncompleted.

When we start to read this novel, we are shocked by the first scene where the hero, Ryunosuke Tsukue (“机龍之助”), kills an old male pilgrim on the top of Dai Bosatsu pass without any specific reasons. He further kills Fuminojo Utsuki by a match at a shrine and kidnaps Fuminojo’s wife and rapes her. You may think then this novel is a picaresque roman, but the hero is not at all jovial but very nihilistic. He will become blind later by an accident, but he still keeps killing many innocent people without clear motives.

Although we classify the novel as “public” romance, this novel is rather favored by intellectual people, as Hiroshi Nakatani (“中谷博” ) pointed out. In 1910, Taigyaku affair (“大逆事件”) occurred and Shusui Kotoku (“幸徳秋水”) and his fellows were sentenced to death by the suspicion that they planned to assassinate the emperor of Meiji. The suppression was much strengthened after the affair, and many intellectual people (among them there were many socialists or anarchists) felt depressed. For them, the acts of Ryunosuke, who kills people disregarding conventional morals completely, were kinds of relief.

The novel was turned into a play by Shinkokugeki (“新国劇”) in 1921, and the sword actions in the play made this novel and Ryunosuke Tsukue very popular. It has been so far picturized as well for five times, though all of them handle just early parts of the novel. Through the play and the movies, Ryunosuke Tsukue became a typical character type in Japanese public romance, and we can find many mimics.

Because the intellectual right of the author has already expired, you can read this novel on the internet. As for English translation, I don’t think it has been released, unfortunately. If you try to understand public romance in Japan, however, this work is a must-read.

P.S.

I found an English translsation by C. S. Bavier at a museum in Hamura city. (Hamura is Kaizan Nakazato’s birthplace). It was released in 1929 as one volume book. Perhaps it might be a digest version or a translation of the beginning part. (August 14, 2018)

Public romance in Japan (2) — some backgrounds

If you ask some Japanese now about the definition of “大衆小説” (popular literature), answers might be much diversified and vague. There could be no more clear distinction between “pure” literature and popular literature. Regarding the popular literature in its early stage, namely public romance in my word, however, its existence was obviously clear and prominent in the total literature in Japan. Before explaining the details of public romance, let me clarify some backgrounds why it became so popular in Taisho period (1912 – 1926):

(1) Taisho period is often referred with the word “democracy”. (Taisho democracy) Democracy in Japan has not started first since after World War II, but it has its origin in Taisho period. The first universal suffrage was given to all adult males for the first time in 1925. It means common people’s power was strengthened more and more during Taisho period.

(2) Along with the development of democracy, many newspapers started their business from around the end of 19th century. They definitely needed catchy entertainment to attract more readers.

(3) For the above mentioned purpose, some newspapers serialized stenography of “Kodan” (講談). Kodan is a traditional art of story-telling in Japan, mainly of anecdotes of historically famous person. Many tellers of Kodan at that time protested them as infringements of their intellectual right. The accused newspaper companies had to explore some alternatives.

It is important that public romance was called “new Kodan” in the beginning, and it replaced stenography of Kodan in offering entertainment to the readers of newspapers.