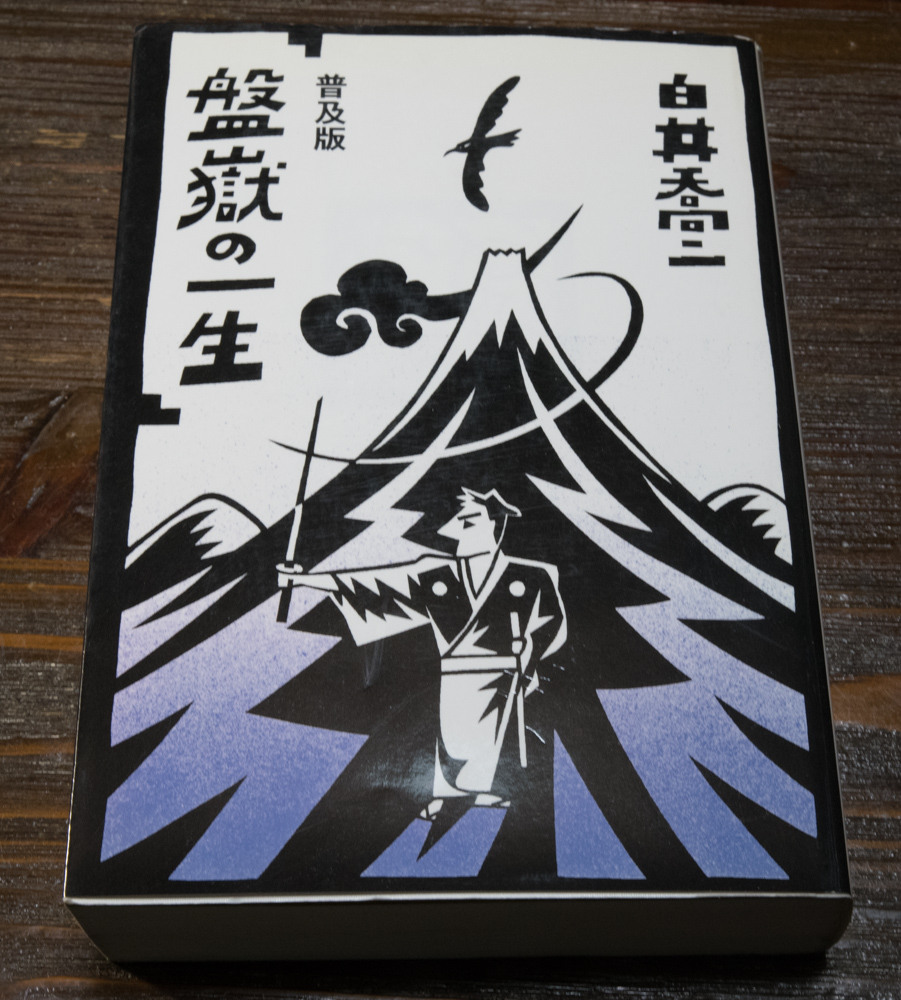

Let me introduce today one of the most impressive novels of Kyoji Shirai: Bangaku no Issho (The life of Bangaku, “盤嶽の一生”). This novel is a collection of short stories featuring Bangaku that Kyoji wrote for several magazines from 1932 to 1935.

Let me introduce today one of the most impressive novels of Kyoji Shirai: Bangaku no Issho (The life of Bangaku, “盤嶽の一生”). This novel is a collection of short stories featuring Bangaku that Kyoji wrote for several magazines from 1932 to 1935.

As the title shows, this novel describes the life of Bangaku Ajigawa (“阿地川盤嶽”), a lone wolf Samurai worrier, who loves rightness and always try to find it and is eventually betrayed. He was born in Bushu (the curent Saitama-Tokyo-Kanagawa area) and lost his father at 12 years old and his mother at 14. After the death of his parents, he was raised by his uncle, but because the daughter of his uncle (namely his cousin) disliked him much, he left his uncle’s house when he became an adult. Since his skill of swordplay reached the expert level when he was 26 years old, his master gave him a noted sword named Heki Mitsuhira (“日置光平”) .

As I wrote in my introduction of Kyoji Shirai’s life, Kyoji inherited the sense of justice from his father who was a policeman when he was born. Bangaku can be considered to be an alter ego of Kyoji. All Christians know the Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.” (Mattew 5.6, KJV). Bangaku is truly one of those who do hunger and thirst after righteousness. If he were a Christian, he might have been filled, but he was not.

Repeated stories of Bangaku that he expects righteousness and he is finally betrayed and disappointed are funny but sad at the same time. For example, when he was living in a slum of the Edo city, he sympathized with miserable workers of a match factory. Since he had some scientific knowledge, he tried to construct an automated machine of match production in order to reduce the heavy work of the workers. When the machine was completed, however, the owner of the factory fired many workers because he can save them by the power of the machine. If we see another example, Bangaku tried once a fortune-telling play by throwing some unglazed dishes (fortune is judged by how dishes broke) because he thought that such thing can be completely coincidental and no human malicious intention is included. The truth was, however, the fortune-teller was preparing several patterns of broken dishes in advance and was selecting the results according to the economical status of the customer.

Bangaku gradually lost any expectation for adults and started to hope for young people. But some young guys betrayed him bitterly and then he started to hope for children, or finally for babies. All his trials were not satisfactory at all.

These stories had not been finished. IMHO, the author, Kyoji, could not find out an appropriate end for these stories, or he might have thought that Bangaku, a kind of dreamer, should wander in the limbo between expectation and disappointment eternally.

This novel was picturized twice and made to a series of TV drama also twice.

The first movie was taken by Sadao Yamanaka in 1933. Sadao Yamanaka was a gifted movie director but died as a soldier in China at the age just 29. While Kyoji Shirai was not satisfied with most movies based on his stories, he evaluated the talent of Sadao Yamanaka very highly. Although the film itself was lost by war, there was a legendary scene in the movie where some thieves of watermelon (Bangaku was having his eyes on a watermelon field in the night) act like rugby players passing a watermelon from one to another. Kon Ichikawa, a Japanese movie director who picturized the first Tokyo Olympic in 1964, watched this movie of Bangaku when he was a child, and he scripted for the TV drama of Bangaku broadcasted in 2002. Bangaku was played by Koji Yakusho (“役所広司”).

「Bangaku no Issho (The life of Bangaku) by Kyoji Shirai」への1件のフィードバック