During an emerging stage of public romance, another outstanding novelist was Kyoji Shirai (“白井喬二”) (1889 – 1980). Not only he created some great works one after another such as “Shimpen Goetsu Zoshi” (“神変呉越草子”) (1922 – 1923), “Shinsen-gumi” (“新撰組”) (1924 – 1925), or “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, A shadow standing on Mt. Fuji) (1924 – 1927), he also started to use the word “大衆” newly as the translation of an English word “public”, adding it a new reading as “Taishu” instead of the conventional “Daisu” or “Daiju” that meant a group of Buddhist monks, and thus triggered that the word “大衆文学” (Taishu Bungaku, literature for common people) was created by the then media.

During an emerging stage of public romance, another outstanding novelist was Kyoji Shirai (“白井喬二”) (1889 – 1980). Not only he created some great works one after another such as “Shimpen Goetsu Zoshi” (“神変呉越草子”) (1922 – 1923), “Shinsen-gumi” (“新撰組”) (1924 – 1925), or “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, A shadow standing on Mt. Fuji) (1924 – 1927), he also started to use the word “大衆” newly as the translation of an English word “public”, adding it a new reading as “Taishu” instead of the conventional “Daisu” or “Daiju” that meant a group of Buddhist monks, and thus triggered that the word “大衆文学” (Taishu Bungaku, literature for common people) was created by the then media.

The reason I use “public romance” here is that the word “大衆” was originally the translation of “public” and most works appeared in this stage were to be regarded rather romances than novels.

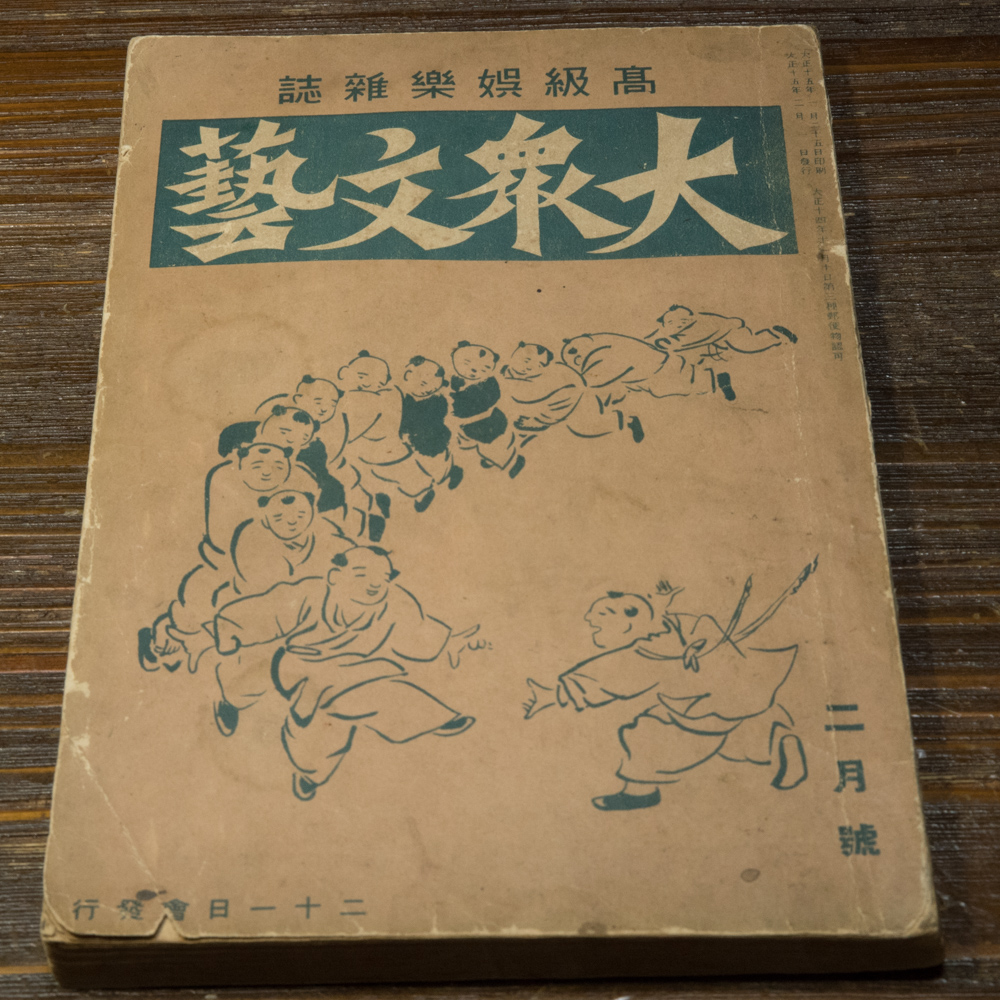

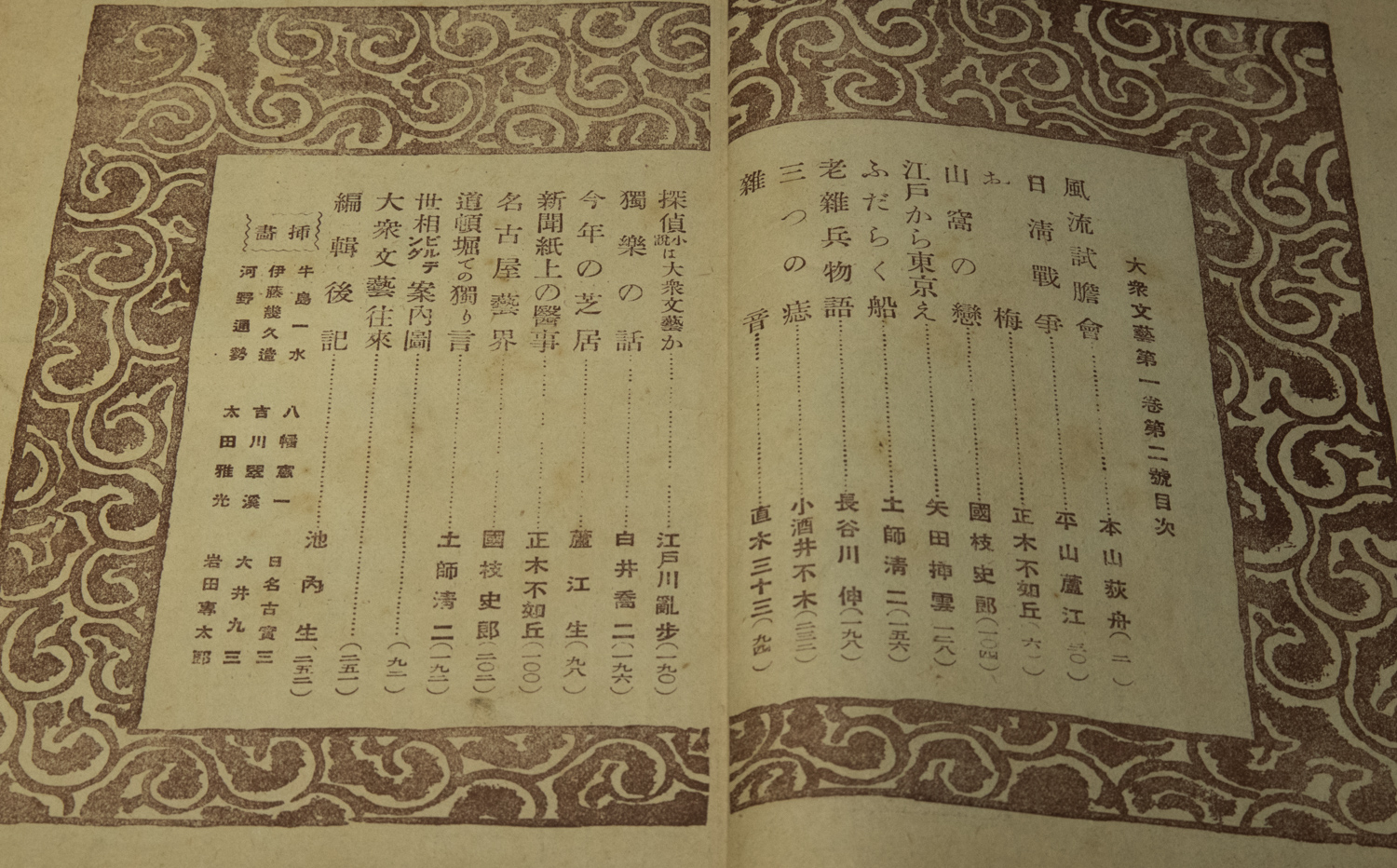

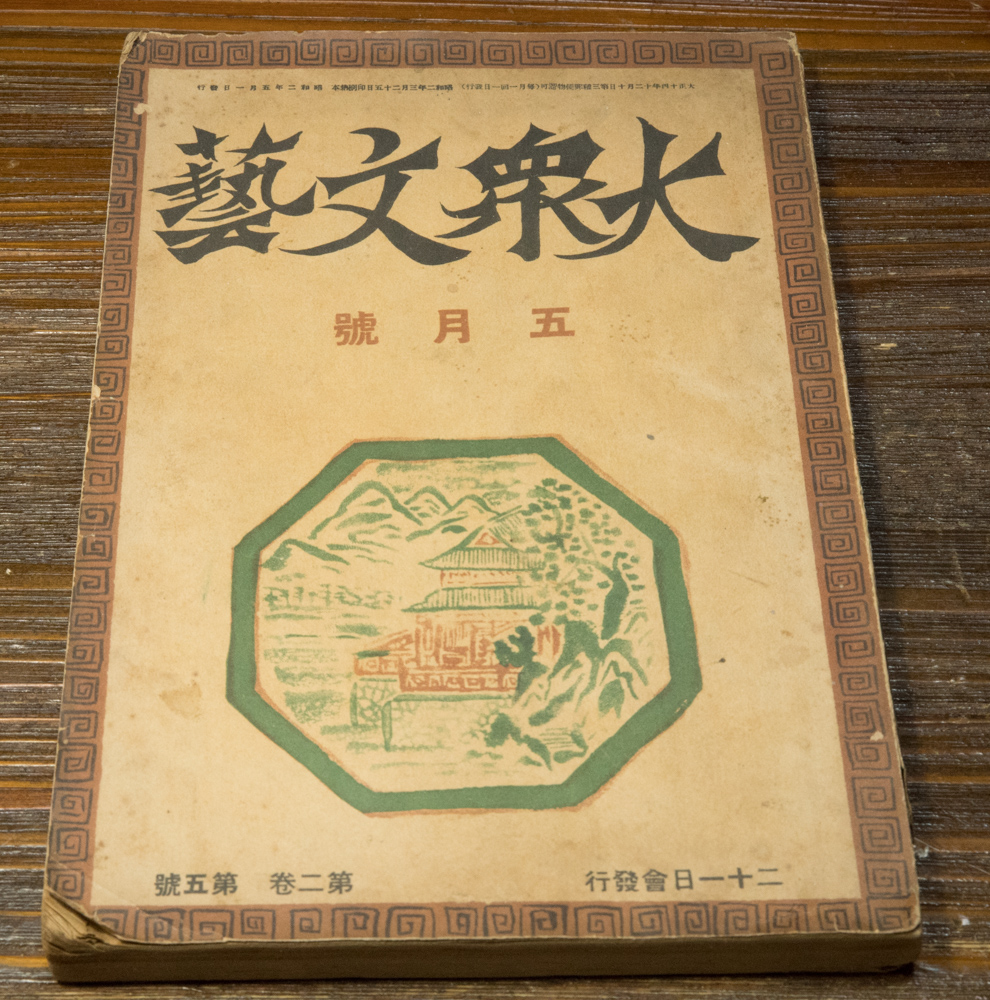

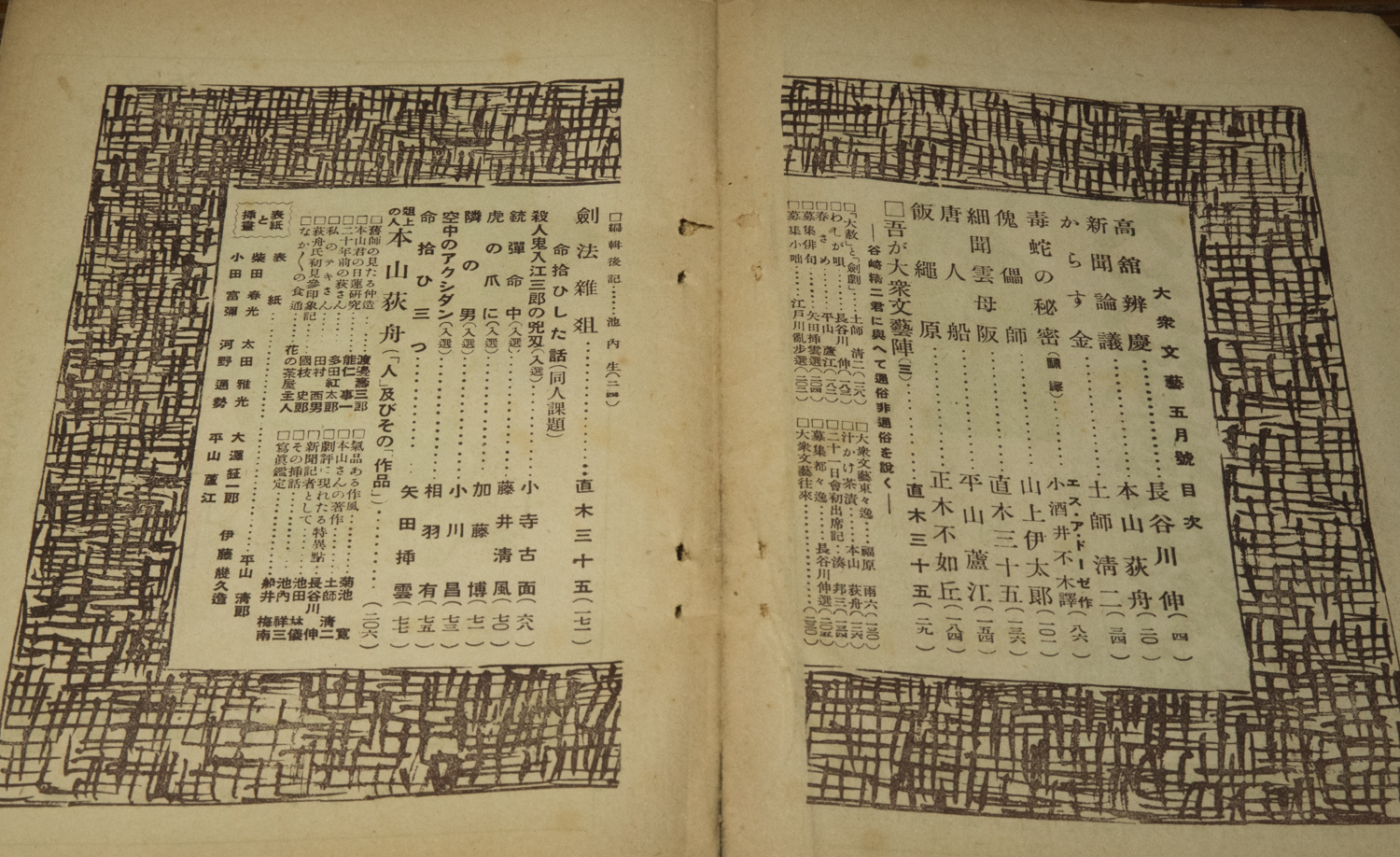

He also initiated a social gathering of public romance novelists in 1925 named “Niju-ichi-nichi kai” (“二十一日会”, a party of twenty first day). The members were, Kyoji Shirai, Shin Hasegawa (“長谷川伸”), Shiro Kunieda (“国枝史郎”), Sanju-san Naoki (“直木三十三”, he changed the name later to Sanju-go Naoki (“直木三十五”)), Rampo Edogawa (“江戸川乱歩”), Fuboku Kosakai (“小酒井不木”), Tekishu Motoyama (“本山荻舟”), Roko Hirayama (“平山蘆江”), Fujokyu Masaki (正木不如丘”), Soun Yada (“矢田挿雲”), and Seiji Haji (“土師清二”). Except Rampo, Fuboku, and Fujokyu, all of them were novelists of period romances. Although Rampo Edogawa was a writer of early-stage detective novels in Japan, that genre was also classified as a type of public romance at that time. From 1926, the party started to publish a magazine named “Taishu Bungei” (“大衆文芸”). (See the pictures.) With the magazine, they presented the emergence of a new genre in the Japanese literature.

コンテンツへスキップ

T-maru's photo blog 書籍レビュー(特に白井喬二、小林信彦)、囲碁、音楽、昔のSF系TVドラマ、野鳥の写真などの話題をお届けしています。 This site offers review of books (especially of Kyoji Shirai and Nobuhiko Kobayashi), of music, old Sci-Fi TV dramas, topics related to Go (board game), and photos of birds.