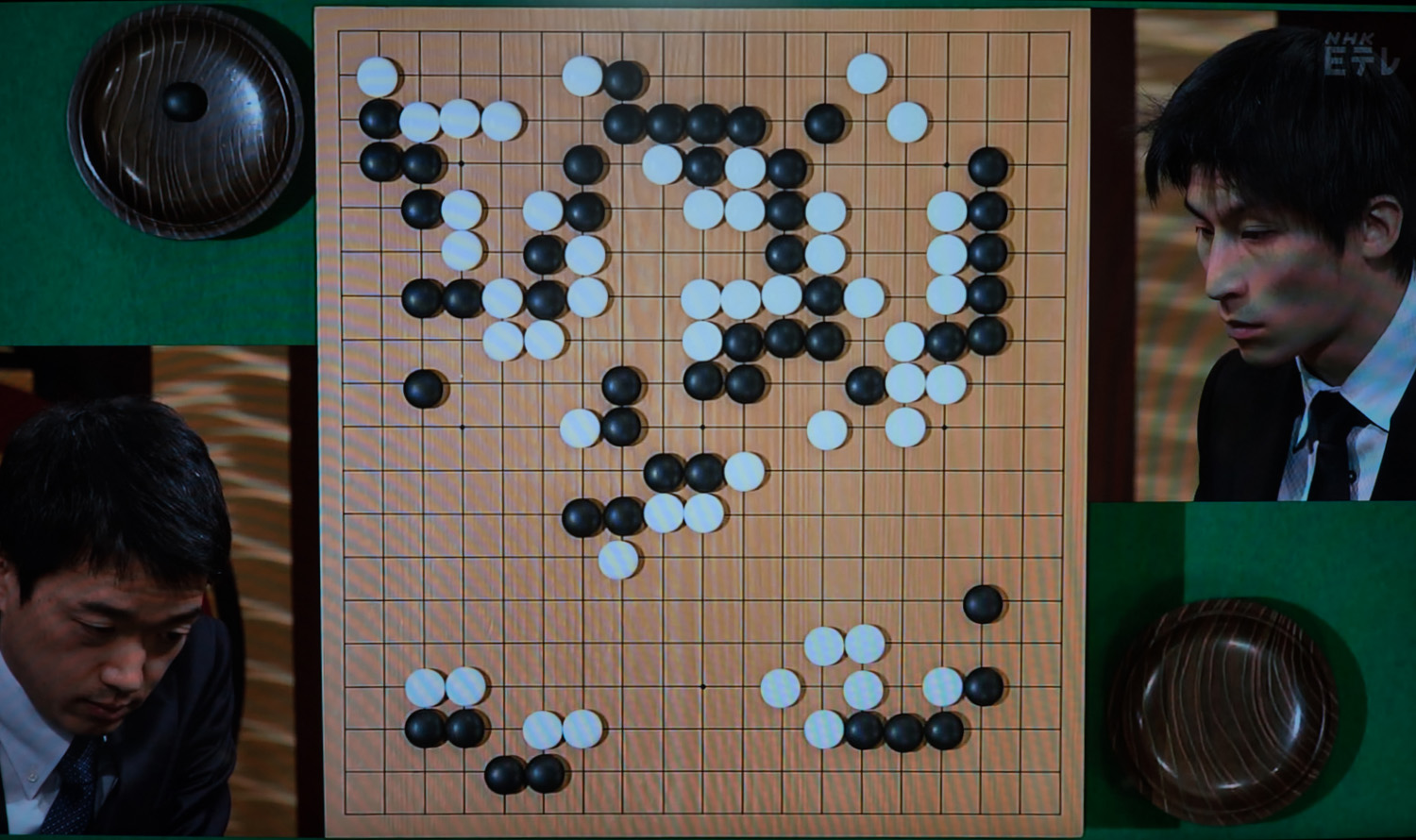

本日のNHK杯戦の囲碁は、黒番が中野泰宏9段、白番が張栩名人の対局です。布石では黒が実利、白が厚みという、二人の棋風とはちょっと違う展開になりました。左上隅を巡る折衝で、黒が妥協して打ったので白は黒2子を一応取った形になりました。しかし周りの状況次第でこの半分取られた黒を動き出して白を切断するのが黒の狙いでした。その後、白は上辺から中央に延びる黒に覗きを打ちました。黒は素直に継がず反発しましたが、白から上辺へのケイマを打たれ、上辺の一部をもぎ取る手と中央の切断を見合いにされました。その結果上辺の黒は単体では一眼しかなく、黒はもがいて先ほどの半取られの2子の所に利かしを打ちました。この結果黒は活きましたが、2子が完全に取られ、白が非常に厚くなりました。更に白は中央の孤立した黒を攻めて中央に大きな地模様を作りました。更に左下隅の黒に利かしていきましたが、結局黒は勝負手で左下隅を捨て、その替わりに中央の白の一部を取り込もうとしました。しかし白は中央も頑張って黒に何も与えず、ここで黒の投了となりました。

本日のNHK杯戦の囲碁は、黒番が中野泰宏9段、白番が張栩名人の対局です。布石では黒が実利、白が厚みという、二人の棋風とはちょっと違う展開になりました。左上隅を巡る折衝で、黒が妥協して打ったので白は黒2子を一応取った形になりました。しかし周りの状況次第でこの半分取られた黒を動き出して白を切断するのが黒の狙いでした。その後、白は上辺から中央に延びる黒に覗きを打ちました。黒は素直に継がず反発しましたが、白から上辺へのケイマを打たれ、上辺の一部をもぎ取る手と中央の切断を見合いにされました。その結果上辺の黒は単体では一眼しかなく、黒はもがいて先ほどの半取られの2子の所に利かしを打ちました。この結果黒は活きましたが、2子が完全に取られ、白が非常に厚くなりました。更に白は中央の孤立した黒を攻めて中央に大きな地模様を作りました。更に左下隅の黒に利かしていきましたが、結局黒は勝負手で左下隅を捨て、その替わりに中央の白の一部を取り込もうとしました。しかし白は中央も頑張って黒に何も与えず、ここで黒の投了となりました。

ブラッドリー・クーパーの「アリー/スター誕生」

「アリー/スター誕生」を観ました。Eigoxの先生が勧めてくれたので観てみました。タイトル通りの単純なサクセスストーリーかと思ったら、きわめてシリアスな物語でした。要するに、「酒とバラの日々」とか「失われた週末」です。ジミーというミュージシャンがアリーという女性の作詞・作曲の能力と歌唱力を見出し、自分のコンサートに彼女を引っ張り出して、彼女が有名プロデューサーに見出されるきっかけを作ります。しかし彼はステージの前にジンをあおらないと演奏出来ないアルコール依存で、おまけにドラッグ中毒でした。(まあ、アートペッパーです。)彼女が成功する一方で彼の依存は強まっていき、二人は結婚しますが、アリーがグラミー賞の新人賞を受賞したそのステージで、彼は極度に酔っぱらっていて失態を演じ、ついに施設に入れられます。その後は書きませんが、私は高校時代からの親友を、アルコール依存で亡くしていますので、とてもお気楽には観られませんでした。レディーガガについては、私は全くファンではありませんが、その歌唱力と曲作りの才能は素晴らしいと思います。でも、あの変なセクシー路線が好きになれません。あまり美人タイプではない女性歌手はアメリカではどうしてもああいう形で売り出されてしまうんだろうなと思います。

「アリー/スター誕生」を観ました。Eigoxの先生が勧めてくれたので観てみました。タイトル通りの単純なサクセスストーリーかと思ったら、きわめてシリアスな物語でした。要するに、「酒とバラの日々」とか「失われた週末」です。ジミーというミュージシャンがアリーという女性の作詞・作曲の能力と歌唱力を見出し、自分のコンサートに彼女を引っ張り出して、彼女が有名プロデューサーに見出されるきっかけを作ります。しかし彼はステージの前にジンをあおらないと演奏出来ないアルコール依存で、おまけにドラッグ中毒でした。(まあ、アートペッパーです。)彼女が成功する一方で彼の依存は強まっていき、二人は結婚しますが、アリーがグラミー賞の新人賞を受賞したそのステージで、彼は極度に酔っぱらっていて失態を演じ、ついに施設に入れられます。その後は書きませんが、私は高校時代からの親友を、アルコール依存で亡くしていますので、とてもお気楽には観られませんでした。レディーガガについては、私は全くファンではありませんが、その歌唱力と曲作りの才能は素晴らしいと思います。でも、あの変なセクシー路線が好きになれません。あまり美人タイプではない女性歌手はアメリカではどうしてもああいう形で売り出されてしまうんだろうなと思います。

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”The Silent Saboteurs”

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”The Silent Saboteurs”を観ました。この回でうれしかったのはジョージ・タケイが出ていたことです。そうです「宇宙大作戦」でスールー(カトー)を演じていた人です。「宇宙大作戦」(スター・トレックのオリジナル・シーズン)は1966年からなんで、このシービュー号の方が早いと思います。お話はアメリカの金星探査船が地球に帰還する時に謎のエネルギーを受けて制御不能になり爆発するという事故を起こします。これがまた「某国」の陰謀だということで、クレーン艦長以下3名がミニサブでアマゾン川流域に向かいます。そこで落ち合う筈なのが何故か中国人で、その偽物役がジョージ・タケイです。ジョージ・タケイ以外にもう一人中国人女性が現れ、そちらも落ち合う筈の人間の名前を名乗ります。それで結局どちらが本物なのかということでストーリーを引っ張ります。最後は敵の怪エネルギー発信基地を爆破して、もう1機の金星探査船は無事に地球に帰還するという話です。

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”The Silent Saboteurs”を観ました。この回でうれしかったのはジョージ・タケイが出ていたことです。そうです「宇宙大作戦」でスールー(カトー)を演じていた人です。「宇宙大作戦」(スター・トレックのオリジナル・シーズン)は1966年からなんで、このシービュー号の方が早いと思います。お話はアメリカの金星探査船が地球に帰還する時に謎のエネルギーを受けて制御不能になり爆発するという事故を起こします。これがまた「某国」の陰謀だということで、クレーン艦長以下3名がミニサブでアマゾン川流域に向かいます。そこで落ち合う筈なのが何故か中国人で、その偽物役がジョージ・タケイです。ジョージ・タケイ以外にもう一人中国人女性が現れ、そちらも落ち合う筈の人間の名前を名乗ります。それで結局どちらが本物なのかということでストーリーを引っ張ります。最後は敵の怪エネルギー発信基地を爆破して、もう1機の金星探査船は無事に地球に帰還するという話です。

正本の相出刃、研ぎ直し

正本の相出刃、日本刀研ぎのプロセスは一応一通りやったんですが、その結果としてすっかり刃先が丸くなって(多分刃艶・地艶の工程で刃先も削ってしまったんだと思います)、観賞用としてはともかく実用としては大いに問題あるので、全部研ぎ直しました。今回はわざとすべて人造砥石で、ナニワのセラミック700番、キングハイパー1000番、ナニワの化学砥石4000番に、キングのS1の8000番という4種です。結果、ぴかぴかの光沢あり包丁になりました。内曇が名前の通り、刃の光を曇らせ、人造砥石はその反対で光沢系になるということが分かりました。まあ切れ味はまったく問題なく戻りましたが、私の研ぎの課題はもっと仕上がりの見た目を良くすることですね。

正本の相出刃、日本刀研ぎのプロセスは一応一通りやったんですが、その結果としてすっかり刃先が丸くなって(多分刃艶・地艶の工程で刃先も削ってしまったんだと思います)、観賞用としてはともかく実用としては大いに問題あるので、全部研ぎ直しました。今回はわざとすべて人造砥石で、ナニワのセラミック700番、キングハイパー1000番、ナニワの化学砥石4000番に、キングのS1の8000番という4種です。結果、ぴかぴかの光沢あり包丁になりました。内曇が名前の通り、刃の光を曇らせ、人造砥石はその反対で光沢系になるということが分かりました。まあ切れ味はまったく問題なく戻りましたが、私の研ぎの課題はもっと仕上がりの見た目を良くすることですね。

土佐の皮むき包丁

毎日、一番良く使っている土佐の皮むき包丁(両刃)。当然一番良く研いでいる包丁でもあって(刃渡りが短い{75mm}ので、研ぐ時場所を変えながら研ぐ必要がなく楽です)、使ってまだ1ヵ月ぐらいにもかかわらず、かなり減っています。左がオリジナル、右が現在の状態。この包丁、実が固くて、そのため皮も固い富有柿を剥くのには最適です。他の包丁を使う気がしません。

毎日、一番良く使っている土佐の皮むき包丁(両刃)。当然一番良く研いでいる包丁でもあって(刃渡りが短い{75mm}ので、研ぐ時場所を変えながら研ぐ必要がなく楽です)、使ってまだ1ヵ月ぐらいにもかかわらず、かなり減っています。左がオリジナル、右が現在の状態。この包丁、実が固くて、そのため皮も固い富有柿を剥くのには最適です。他の包丁を使う気がしません。

日本刀風包丁の仕上げ

日本刀風包丁の仕上げにちょっと前からチャレンジしています。包丁を内曇砥と鳴滝砥で研いだ後、それぞれを薄くスライスし、小さくした地艶、刃艶というので刃の所を磨きます。そして今日「拭い」の液(「古色」という古刀風の味わいを出すもの)と磨き棒が届いたので、仕上げを施してみました。拭いの液を刃面に適当に垂らし、それを綿で若干圧力をかけながら拭って、液を地にしみこませるようにします。それが終わったら、新しい真綿で全体を拭い、液の膜がうっすら残るぐらいにします。その後、内曇の地艶を小さくして、それで刃の部分の液を取り去って、刃を光らせます。最後に磨き棒で刃の部分をこすっていって光沢が強くなるようにします。

日本刀風包丁の仕上げにちょっと前からチャレンジしています。包丁を内曇砥と鳴滝砥で研いだ後、それぞれを薄くスライスし、小さくした地艶、刃艶というので刃の所を磨きます。そして今日「拭い」の液(「古色」という古刀風の味わいを出すもの)と磨き棒が届いたので、仕上げを施してみました。拭いの液を刃面に適当に垂らし、それを綿で若干圧力をかけながら拭って、液を地にしみこませるようにします。それが終わったら、新しい真綿で全体を拭い、液の膜がうっすら残るぐらいにします。その後、内曇の地艶を小さくして、それで刃の部分の液を取り去って、刃を光らせます。最後に磨き棒で刃の部分をこすっていって光沢が強くなるようにします。

この包丁は鋼100%ではなく合わせ(本霞)なので、刃文みたいに見えるのは実際には本当の意味の刃文ではなく、鋼と軟鉄の境界線ですが、一応それらしくはなったかな、と思います。「拭い」については最初着色に近いものかと想像していましたが、実際にはやってみたらかすかに色を滲ませる、ぐらいのものでした。

鋼100%の包丁はあまり高くないのを見つけて注文しています。届いたら、また日本刀風仕上げをやってみたいと思います。

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”The Peacemaker”

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”The Peacemaker”を観ました。今回うれしかったのは「タイムトンネル」のカーク所長の俳優が登場したことです。(写真)お話はシリアスで、アメリカはプロトン爆弾の開発に成功し、牛乳箱大の爆弾が水爆の数十倍の威力を持ち、もし机の大きさぐらいのを作れば地球が丸ごと吹っ飛ぶという威力です。しかし、その開発チームにいた研究者が10年前に中国に亡命し、中国でもプロトン爆弾を作っていました。その研究者の意図は、パワーバランスを維持することで世界を平和に保つことでしたが、爆弾が完成するとその研究者は殺されかけます。かろうじて生き延びた研究者はアメリカにコンタクトし、シービュー号が救助に来ることを要請します。その意図は中国が海底にセットしたプロトン爆弾を解体することでした。ネルソン提督とその研究者はそのプロトン爆弾をシービュー号の船内に収納することに成功します。研究者は爆弾を解体しますが、実はそれは彼以外誰にも解体が出来ないようにし、逆に彼だけがその爆弾を爆発させるスイッチを持つことが目的でした。スイッチを握った研究者は、ヨーロッパで行われていた軍縮会議と通信し、全世界の国が武装解除しないとこの爆弾を爆発させると脅します。結局、ネルソン提督はその研究者にボタンを押させ、爆弾が起動する前にそれを何とか無力化するという賭けに出、爆弾からプロトンの容器を取り外し、残った部分をシービュー号の脱出ハッチから放出し、何とか世界の破滅を食い止める、という話です。プロトン爆弾というのは単にSFの世界の話(SFでは反陽子爆弾ですね)ですが、1960年代というのは本当に世界の破滅の危機が日常的に感じられる時代で、その意味でこのドラマのリアリティーがあるのだと思います。

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”The Peacemaker”を観ました。今回うれしかったのは「タイムトンネル」のカーク所長の俳優が登場したことです。(写真)お話はシリアスで、アメリカはプロトン爆弾の開発に成功し、牛乳箱大の爆弾が水爆の数十倍の威力を持ち、もし机の大きさぐらいのを作れば地球が丸ごと吹っ飛ぶという威力です。しかし、その開発チームにいた研究者が10年前に中国に亡命し、中国でもプロトン爆弾を作っていました。その研究者の意図は、パワーバランスを維持することで世界を平和に保つことでしたが、爆弾が完成するとその研究者は殺されかけます。かろうじて生き延びた研究者はアメリカにコンタクトし、シービュー号が救助に来ることを要請します。その意図は中国が海底にセットしたプロトン爆弾を解体することでした。ネルソン提督とその研究者はそのプロトン爆弾をシービュー号の船内に収納することに成功します。研究者は爆弾を解体しますが、実はそれは彼以外誰にも解体が出来ないようにし、逆に彼だけがその爆弾を爆発させるスイッチを持つことが目的でした。スイッチを握った研究者は、ヨーロッパで行われていた軍縮会議と通信し、全世界の国が武装解除しないとこの爆弾を爆発させると脅します。結局、ネルソン提督はその研究者にボタンを押させ、爆弾が起動する前にそれを何とか無力化するという賭けに出、爆弾からプロトンの容器を取り外し、残った部分をシービュー号の脱出ハッチから放出し、何とか世界の破滅を食い止める、という話です。プロトン爆弾というのは単にSFの世界の話(SFでは反陽子爆弾ですね)ですが、1960年代というのは本当に世界の破滅の危機が日常的に感じられる時代で、その意味でこのドラマのリアリティーがあるのだと思います。

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”Leviathan”

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”Leviathan”を観ました。題名のリヴァイアサンはホッブズの本の題名に使われたので有名ですが、元の意味は旧約聖書に出てくる海に住む巨大な怪物です。その題名通り、今回は巨大海洋生物のオンパレードで、巨大シュモクザメ、巨大タコ、巨大イカ、巨大クラゲ、巨大マンタ等々、これまで出てきたのが再度登場している感じです。極めつけは巨大海洋人間!この怪物は海底の研究室で海の裂け目から地球のマントルエネルギーを取り出そうとしていた研究者のなれの果てです。その研究者海底火山の爆発と共に生じた裂け目からエネルギーが噴出していると、自分の研究の成功を確信し、パートナーの女性研究者をネルソン提督の元に送ってシービュー号による支援を求めます。しかしその女性研究者はシービュー号に乗り込むと、キッチンの塩の缶の中に幻覚剤を混ぜます。このためシービュー号の乗員全員が様々な海洋巨大生物を目撃しますが、何故かそれはレーダーには反応せずまた衝突もせずだったり、逆にレーダーには反応するのに肉眼では確認できない、という事態に振り回されます。実はこの海洋巨大生物は海底研究室の周りでは実在しており、この女性研究者は巨大生物に慣れさせるために幻覚剤を使ったと後で告白します。ネルソンと女性研究者はフライング・サブで研究所に駆けつけますが、そこで見たのは通常の人間の3倍以上の高さになった研究者でした。ネルソン提督はシービュー号に連絡しようとしますが、研究者は椅子をネルソン提督と無線機目がけて投げつけます。ネルソンが気絶している間に研究者はさらに巨大になり、外に出ていきます。(何故呼吸が出来るかの説明はありません。)そしてシービュー号を捕らえて破壊しようとします。巨大研究者がシービュー号を足で海底に押しつけ、大きな岩を振り上げシービュー号目がけて投げつけようとしますが、間一髪でクレーン艦長が電撃を命じ男が倒れて岩は研究所を破壊し、研究者は海底の割れ目に消えて行きます。ちょっとゴジラみたいな話です。しかしこれは撮影するの大変だったと思います。

「原子力潜水艦シービュー号」の”Leviathan”を観ました。題名のリヴァイアサンはホッブズの本の題名に使われたので有名ですが、元の意味は旧約聖書に出てくる海に住む巨大な怪物です。その題名通り、今回は巨大海洋生物のオンパレードで、巨大シュモクザメ、巨大タコ、巨大イカ、巨大クラゲ、巨大マンタ等々、これまで出てきたのが再度登場している感じです。極めつけは巨大海洋人間!この怪物は海底の研究室で海の裂け目から地球のマントルエネルギーを取り出そうとしていた研究者のなれの果てです。その研究者海底火山の爆発と共に生じた裂け目からエネルギーが噴出していると、自分の研究の成功を確信し、パートナーの女性研究者をネルソン提督の元に送ってシービュー号による支援を求めます。しかしその女性研究者はシービュー号に乗り込むと、キッチンの塩の缶の中に幻覚剤を混ぜます。このためシービュー号の乗員全員が様々な海洋巨大生物を目撃しますが、何故かそれはレーダーには反応せずまた衝突もせずだったり、逆にレーダーには反応するのに肉眼では確認できない、という事態に振り回されます。実はこの海洋巨大生物は海底研究室の周りでは実在しており、この女性研究者は巨大生物に慣れさせるために幻覚剤を使ったと後で告白します。ネルソンと女性研究者はフライング・サブで研究所に駆けつけますが、そこで見たのは通常の人間の3倍以上の高さになった研究者でした。ネルソン提督はシービュー号に連絡しようとしますが、研究者は椅子をネルソン提督と無線機目がけて投げつけます。ネルソンが気絶している間に研究者はさらに巨大になり、外に出ていきます。(何故呼吸が出来るかの説明はありません。)そしてシービュー号を捕らえて破壊しようとします。巨大研究者がシービュー号を足で海底に押しつけ、大きな岩を振り上げシービュー号目がけて投げつけようとしますが、間一髪でクレーン艦長が電撃を命じ男が倒れて岩は研究所を破壊し、研究者は海底の割れ目に消えて行きます。ちょっとゴジラみたいな話です。しかしこれは撮影するの大変だったと思います。

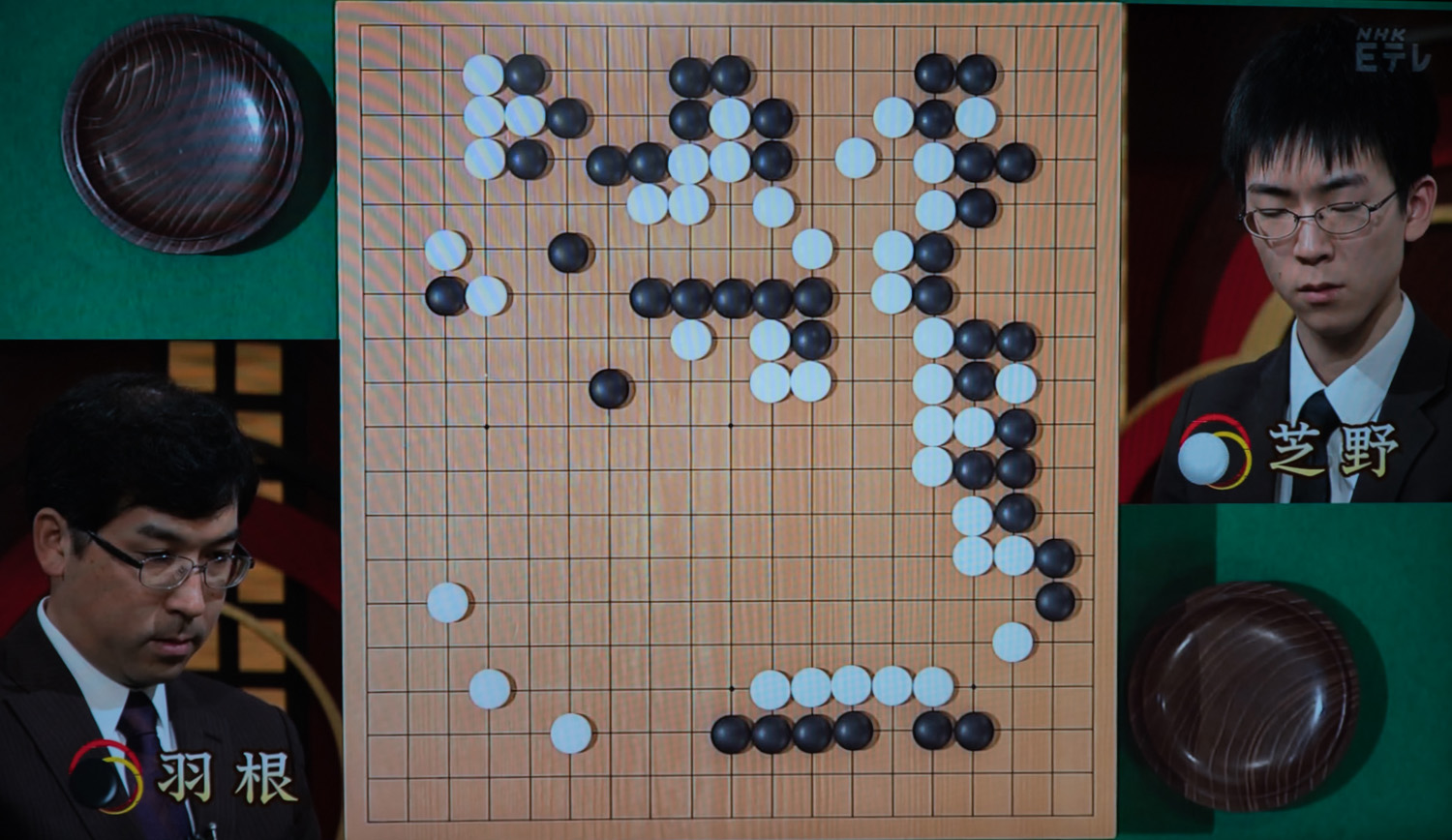

NHK杯戦囲碁 羽根直樹9段 対 芝野虎丸7段

本日のNHK杯戦の囲碁は黒番が羽根直樹9段、白番が芝野虎丸7段という注目の一戦です。布石は羽根9段があくまで従来風のじっくりした布石を目指したのに対し、芝野7段はAI風の手を繰り出し、右下隅に右辺からかかって黒が4間に緩やかに挟んだ時、いきなりその石の左に付けるといういかにも今風の打ち方をしました。羽根9段はそれに対し慌てず騒がずじっくり地を稼いで対抗します。しかし右上隅から右辺での折衝で黒が延びてすかさず白に2目の頭を叩かれたのは失着で、すかさず切り込みを打たれ、右辺下部で白の下がりを先手で利かされたのは問題でした。その後も芝野7段の自由奔放な打ち回しは続き、白が有望な局面になりました。ここで羽根9段は上辺の黒と連絡しながら左辺に進出すれば普通でしたが左上隅で白が星から小ゲイマに開いている石に付けていきました。白は当然その間を割いていきましたが、黒は左辺に地を持って頑張り、中央の黒は上辺から切り離されそうになりながらも、何とか駄目をつながる手を打って辛抱し、結果として形勢を盛り返しました。この辺り若干白が優勢を意識して堅く打ち過ぎたように思います。その後白は右下隅に飛び込む大きなヨセを打ちましたが、羽根9段は後に右辺から出て白が押さえた時に白の一間トビに割り込む手を用意していました。この手は芝野7段は予測しておらず、打たれた時、いつもはポーカーフェイスの芝野7段も一瞬顔色が変わりました。結果として黒は右下隅で白1子をもぎ取り、ここで形勢がはっきり黒良しになりました。中央の白地も最終的には大きくはまとまらず、終わってみれば黒の5目半勝ちでした。羽根9段の後半の逆転が見事でした。

本日のNHK杯戦の囲碁は黒番が羽根直樹9段、白番が芝野虎丸7段という注目の一戦です。布石は羽根9段があくまで従来風のじっくりした布石を目指したのに対し、芝野7段はAI風の手を繰り出し、右下隅に右辺からかかって黒が4間に緩やかに挟んだ時、いきなりその石の左に付けるといういかにも今風の打ち方をしました。羽根9段はそれに対し慌てず騒がずじっくり地を稼いで対抗します。しかし右上隅から右辺での折衝で黒が延びてすかさず白に2目の頭を叩かれたのは失着で、すかさず切り込みを打たれ、右辺下部で白の下がりを先手で利かされたのは問題でした。その後も芝野7段の自由奔放な打ち回しは続き、白が有望な局面になりました。ここで羽根9段は上辺の黒と連絡しながら左辺に進出すれば普通でしたが左上隅で白が星から小ゲイマに開いている石に付けていきました。白は当然その間を割いていきましたが、黒は左辺に地を持って頑張り、中央の黒は上辺から切り離されそうになりながらも、何とか駄目をつながる手を打って辛抱し、結果として形勢を盛り返しました。この辺り若干白が優勢を意識して堅く打ち過ぎたように思います。その後白は右下隅に飛び込む大きなヨセを打ちましたが、羽根9段は後に右辺から出て白が押さえた時に白の一間トビに割り込む手を用意していました。この手は芝野7段は予測しておらず、打たれた時、いつもはポーカーフェイスの芝野7段も一瞬顔色が変わりました。結果として黒は右下隅で白1子をもぎ取り、ここで形勢がはっきり黒良しになりました。中央の白地も最終的には大きくはまとまらず、終わってみれば黒の5目半勝ちでした。羽根9段の後半の逆転が見事でした。

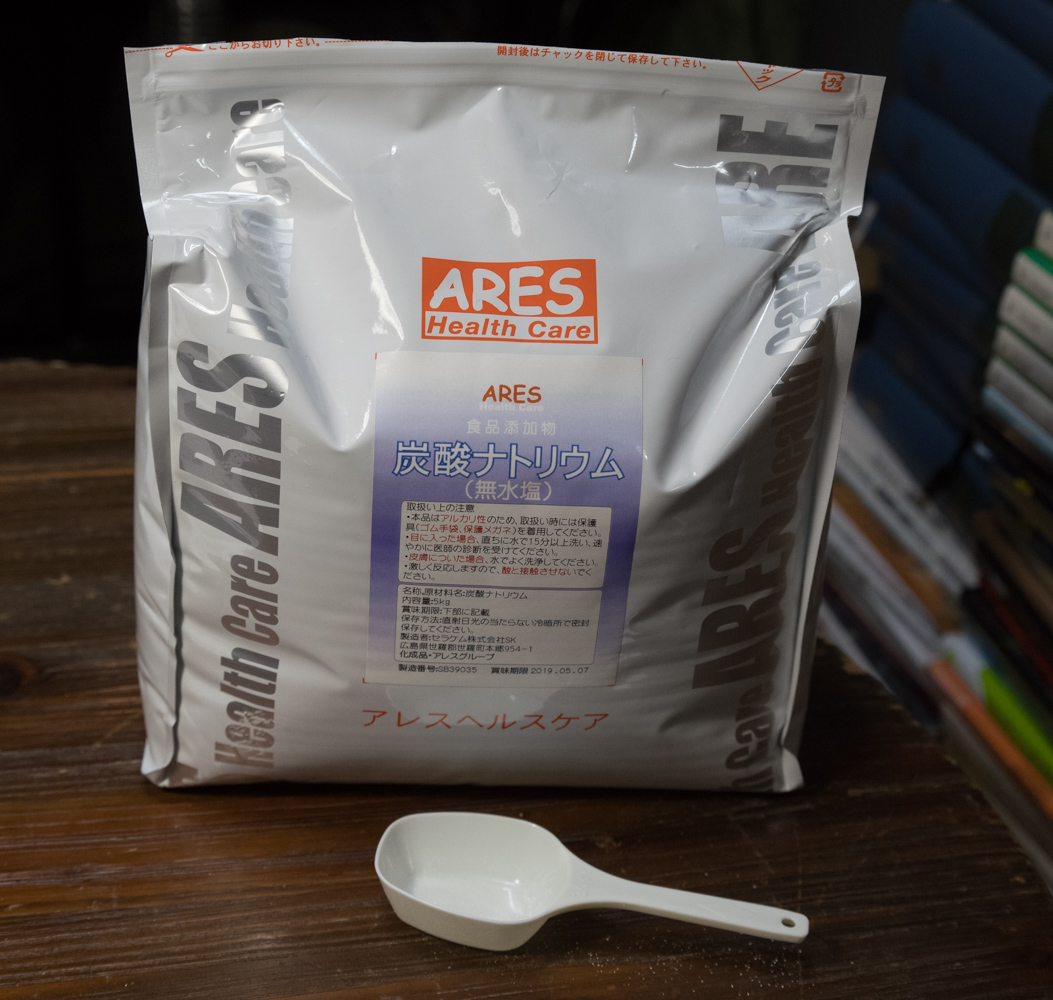

研ぎ水を弱アルカリ性にする。

天然砥石の中には、研ぎ汁が酸性になるものがあり、そういう砥石で鋼の包丁を研ぐと、研いだ後すぐに錆が発生します。手持ちの天然砥石では巣板の2つが、リトマス試験紙でテストしてみたら研ぎ汁が酸性になっていました。それではどうすればいいのか、ということですが、日本刀の研ぎでも同じ現象が発生し、そちらでは研ぎ汁に炭酸ナトリウム(洗濯用ソーダ)を入れて弱アルカリ性にすることで、研ぎ汁の酸性を中和しています。

天然砥石の中には、研ぎ汁が酸性になるものがあり、そういう砥石で鋼の包丁を研ぐと、研いだ後すぐに錆が発生します。手持ちの天然砥石では巣板の2つが、リトマス試験紙でテストしてみたら研ぎ汁が酸性になっていました。それではどうすればいいのか、ということですが、日本刀の研ぎでも同じ現象が発生し、そちらでは研ぎ汁に炭酸ナトリウム(洗濯用ソーダ)を入れて弱アルカリ性にすることで、研ぎ汁の酸性を中和しています。

それで炭酸ナトリウムを注文しましたが、それが届いたので、早速研ぎに使ってみました。取り敢えず研ぎ桶(台所の流しに収まるくらいの桶)に7分目くらいに水を溜めて、写真に写っている添付のスプーンですりきり一杯入れて、pH計でpHを測定したらpH11で明らかにアルカリ性が強すぎます。結局水を3倍くらいに希釈してやっとpH10位になりました。つまり炭酸ナトリウムはアルカリ源としてはかなり強力です。多分研ぎ桶に小さじすりきり一杯くらいで十分と思います。また、手が荒れるのでゴム手袋必須です。強すぎるアルカリ性は砥石にもダメージを与える可能性があります。