Let me introduce today Kyoji Shirai’s best romance, “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, a shadow standing on Mr. Fuji). This romance is not only his best work, but also a big milestone in the history of public romance, or even in all Japanese literature, I should say. The three greatest works in public romance are, “Dai Bosatsu Touge”, “Musashi” (“宮本武蔵”) of Eiji Yoshikawa (“”吉川英治”), and this work.

Let me introduce today Kyoji Shirai’s best romance, “Fuji ni tatsu kage” (“富士に立つ影”, a shadow standing on Mr. Fuji). This romance is not only his best work, but also a big milestone in the history of public romance, or even in all Japanese literature, I should say. The three greatest works in public romance are, “Dai Bosatsu Touge”, “Musashi” (“宮本武蔵”) of Eiji Yoshikawa (“”吉川英治”), and this work.

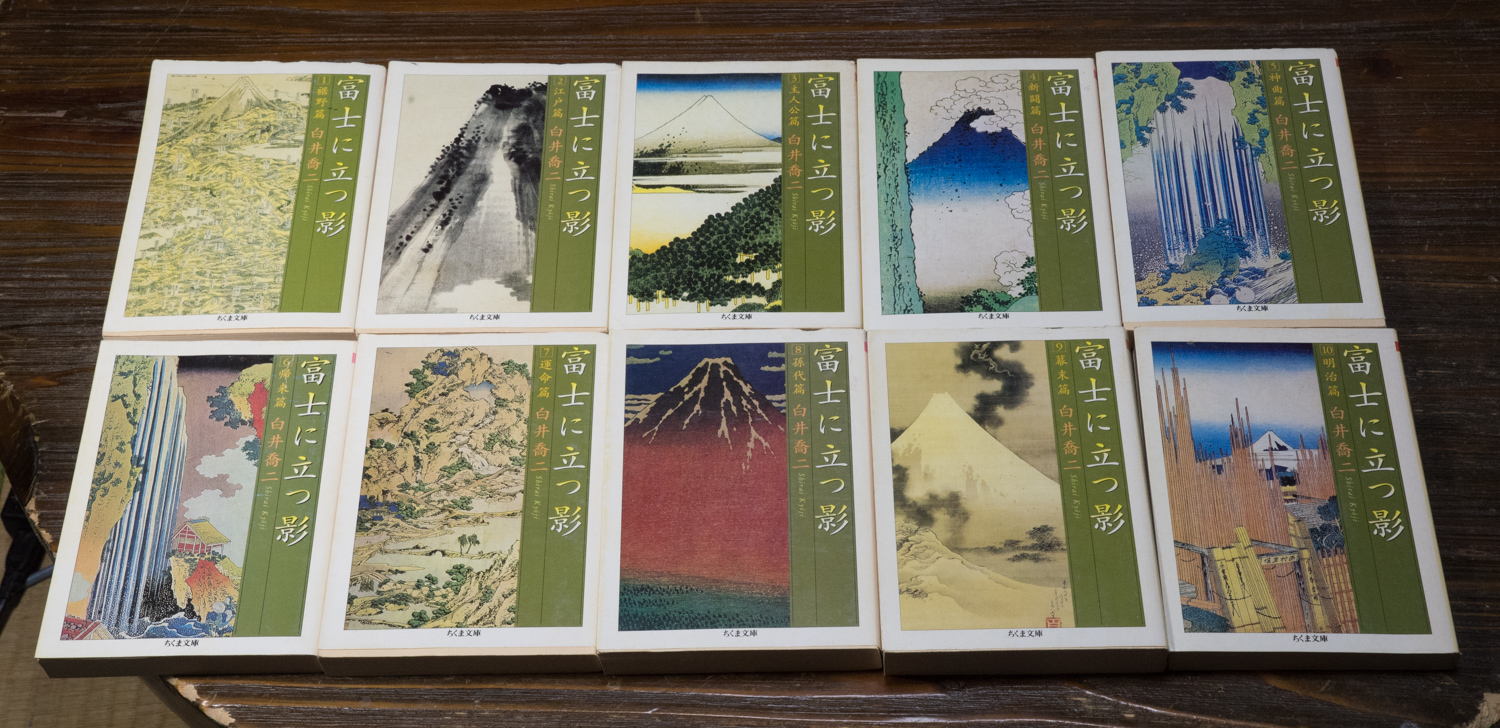

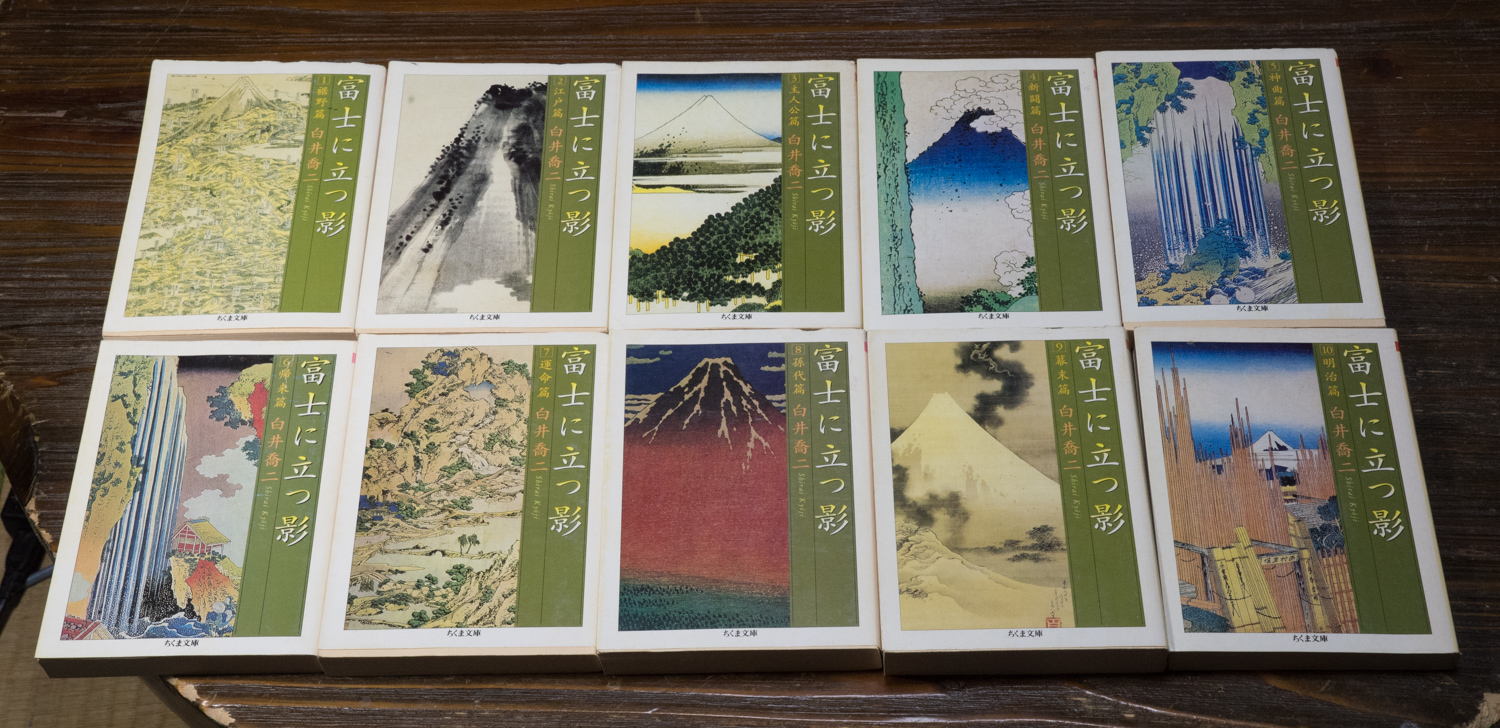

This romance was serialized in the newspaper “Hochi” (“報知新聞”) from July 1924 through July 1927, for more than 1,000 times. (Novels serialized in newspapers are still popular in Japan, but the average period of continuance is just around a half year.) There are ten volumes (also chapters) in Japanese paper book style, as you can see in the photo. The names of ten parts are, 1. Susono-hen (Chapter of the plain at the foot of Mt. Fuji), 2. Edo-hen (Chapter of Edo city), 3. Shujinko-hen (Chapter of the central character), 4. Shinto-hen (Chapter of a new battle), 5. Shinkyoku-hen (Chapter of Divine Comedy), 6. Kirai-hen (Chapter of coming back to Mt. Fuji), 7. Unmei-hen (Chapter of destiny), 8. Sondai-hen (Chapter of grandsons’ generation), 9. Bakumatsu-hen (Chapter of the end of Edo period), and 10. Meiji-hen (Chapter of Meiji period). The romance was sold for more than 3 million copies.

Let me introduce now basic story of this romance. To make a long story (literally) short, this romance describes 68 years’ (1805 – 1873) battles between two families of castle builders, during three generations, namely fathers, sons, and grandsons. The author said that he described “war and peace” based on humanity. The story starts when Tokugawa shogunal government planned to build a new castle in the plain at the foot of Mt. Fuji for the training of their subordinate soldiers in western style. The government summoned two engineers, namely Kikutaro Sato (“佐藤菊太郎”), as a representative of Sanshi-ryu (“賛四流”) school of castle building, and Hakuten Kumaki (“熊木伯典”), as one of Sekishin-ryu (“赤針流”), another dominant school of castle building. The government tries to determine the chief designer of the new castle by the competition between two schools. Until this work, most public romance used fighting by Japanese swords (Chambara) to solve the conflict between two parties. This work, however, adopted debates between two engineers, which was, and still is, a brand-new style. Kikutaro is a young, talented, and honest guy. Hakuten, an older guy, on the other hand, plays very dirty. Most readers expected the victory of Kikutaro, a white-hat, but the author betrays the readers’ expectation, which is very rare in public romance.

The actual hero of this romance appears at first only from the chapter three. The hero, Kimitaro Kumami (“熊木公太郎”) is the son of Hakuten, a quite evil guy. The son, however, is completely different from his father. He is quite honest, decent, always trying to protect the weak, and at the same time a little bit foolish. A critic compared him with Prince Myshkin in Dostoyevsky’s novel “The Idiot”. Both of them are, so to say, holy idiots. This character is quite new and different from the cruel, nihilistic character of “Ryunosuke Tsukue” in “Dai Bosatsu Touge”. This hero brought the romance into a big success, because many readers really loved the character of Kimitaro. In parallel to Kimitaro, Heinosuke Sato (“佐藤兵之助”), the son of Kikutaro, is described as a very smart, bureaucratic type, but rather cruel guy. This is quite a surprising twist that the good side and the evil side turn over in the second generation.

One English teacher at Eigox told me when I introduced this romance to him that this romance sounds similar as Frank Herbert’s “Dune”, which also describes the battles between two families, namely between the Atreides and the Harkonnens. In Dune, however, the Harkonnes are always described as the evil side. In Fuji ni tatsu kage, we cannot simply say that one side is good and the other is bad, and do not know until the end of the story how the battles between two families are settled. There is also a “Romeo and Juliet” type affair between the two families, which makes the story more complex and attractive. In such viewpoints, this romance goes far beyond the realm of usual public romance. Kyoji Shirai aimed at such a high-level literature even the genre was classified as public romance, which was usually considered as vulgar literature.

It is absolutely impossible to describe all charm of this romance here. I strongly hope that this novel will be translated into English for foreign readers someday.

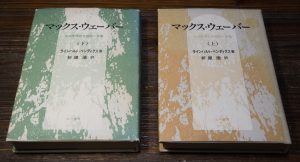

東大の駒場は日本の新約聖書研究では結構重要な役目を果たしています。内村鑑三の無教会派に属していた矢内原忠雄が1949年に教養学部長になり(今は無くなってしまったみたいですが、昔駒場キャンパスには矢内原門というのがありました)、後に東大総長になりますが、その時代に、私の出身学科である教養学科ドイツ科から3人の新約聖書学者が出ています。

東大の駒場は日本の新約聖書研究では結構重要な役目を果たしています。内村鑑三の無教会派に属していた矢内原忠雄が1949年に教養学部長になり(今は無くなってしまったみたいですが、昔駒場キャンパスには矢内原門というのがありました)、後に東大総長になりますが、その時代に、私の出身学科である教養学科ドイツ科から3人の新約聖書学者が出ています。